Feature by Sayuri Govender

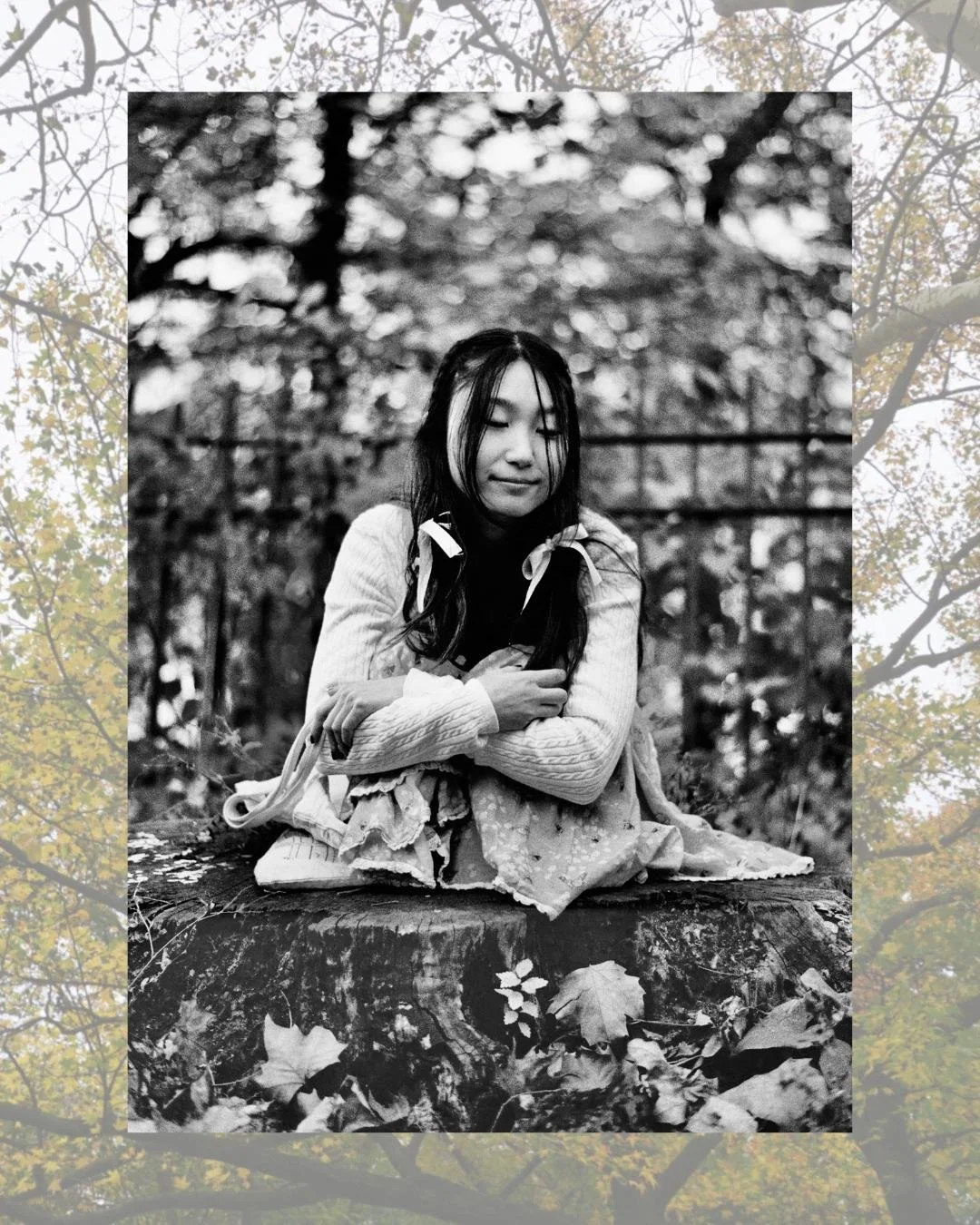

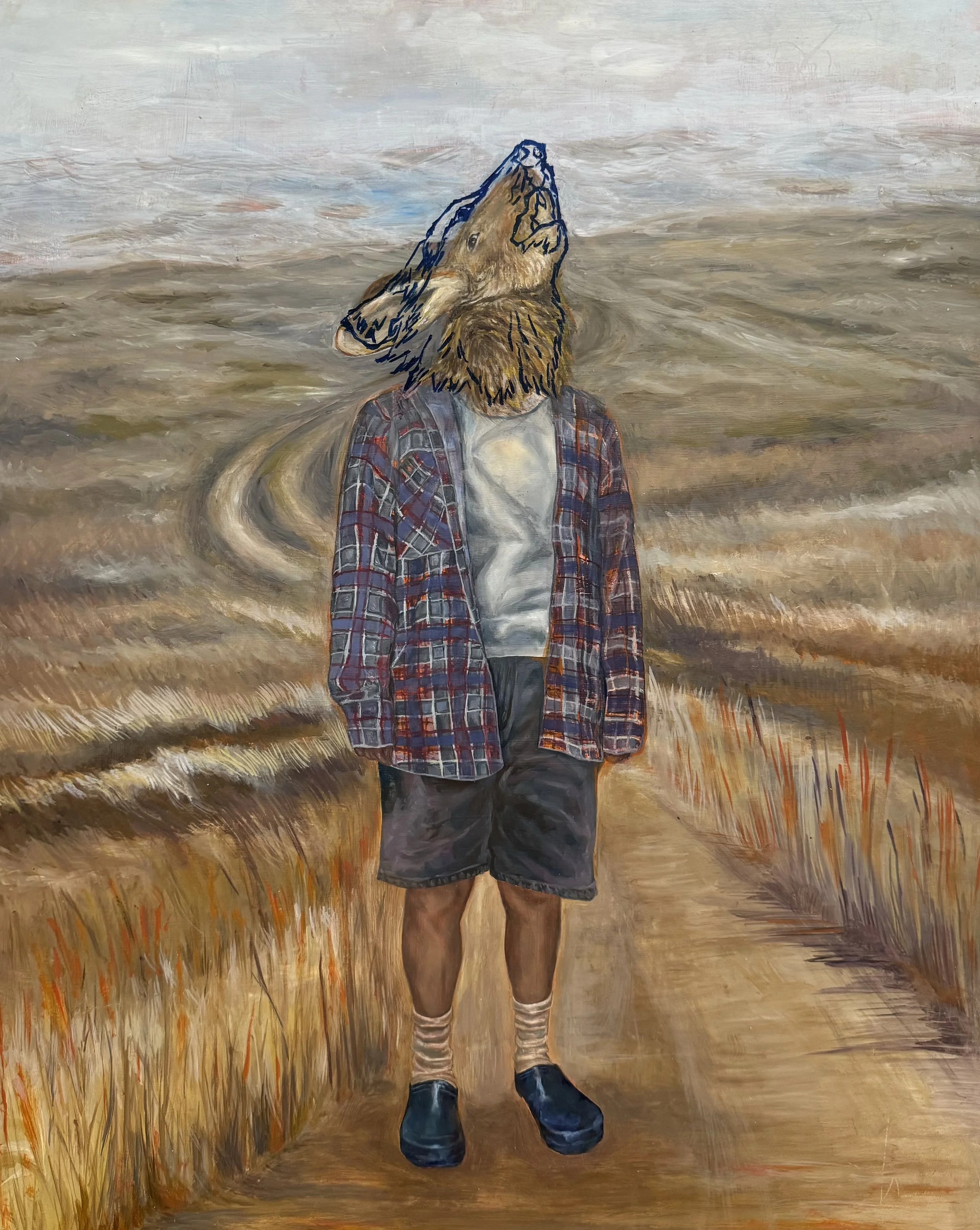

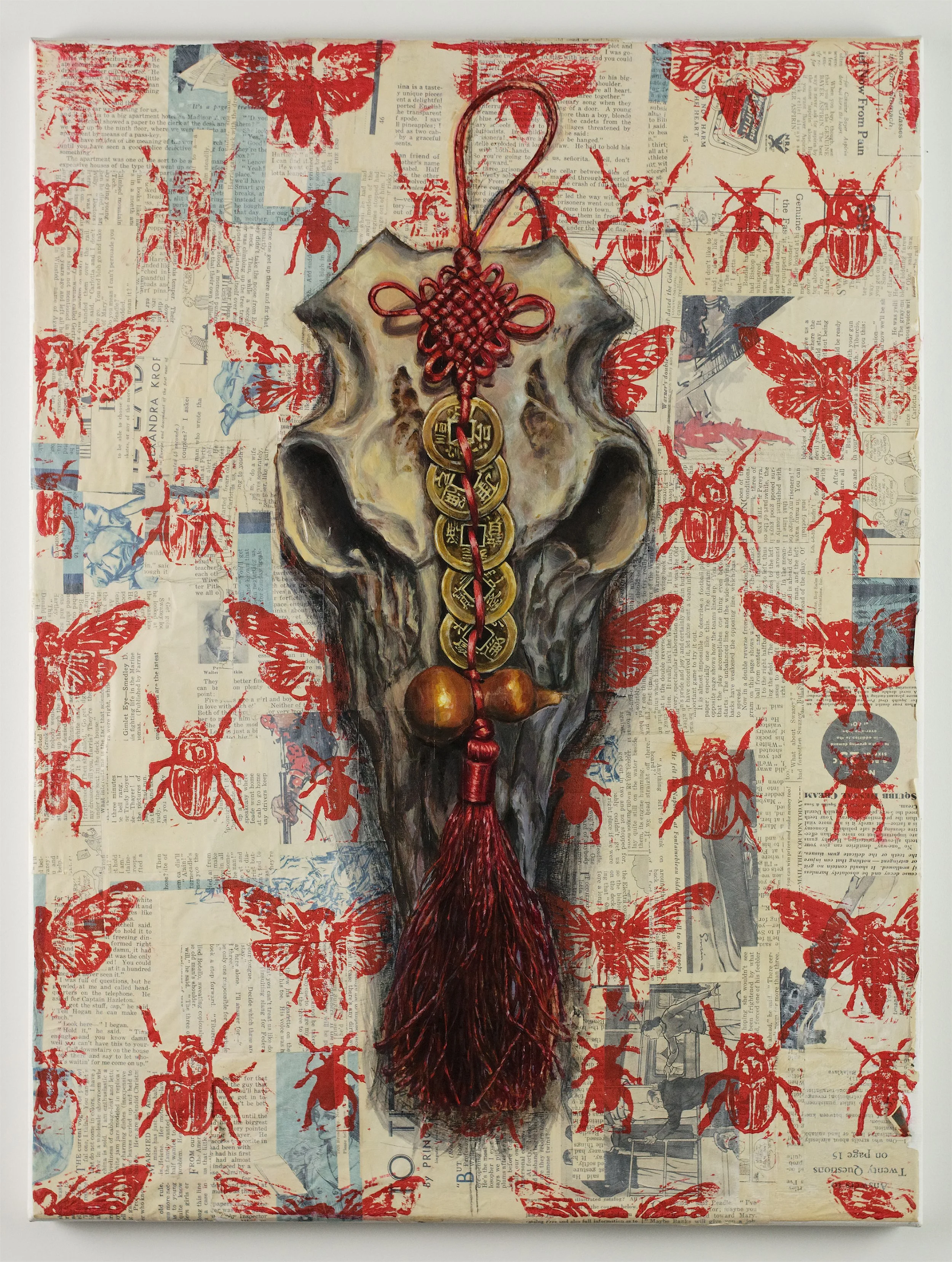

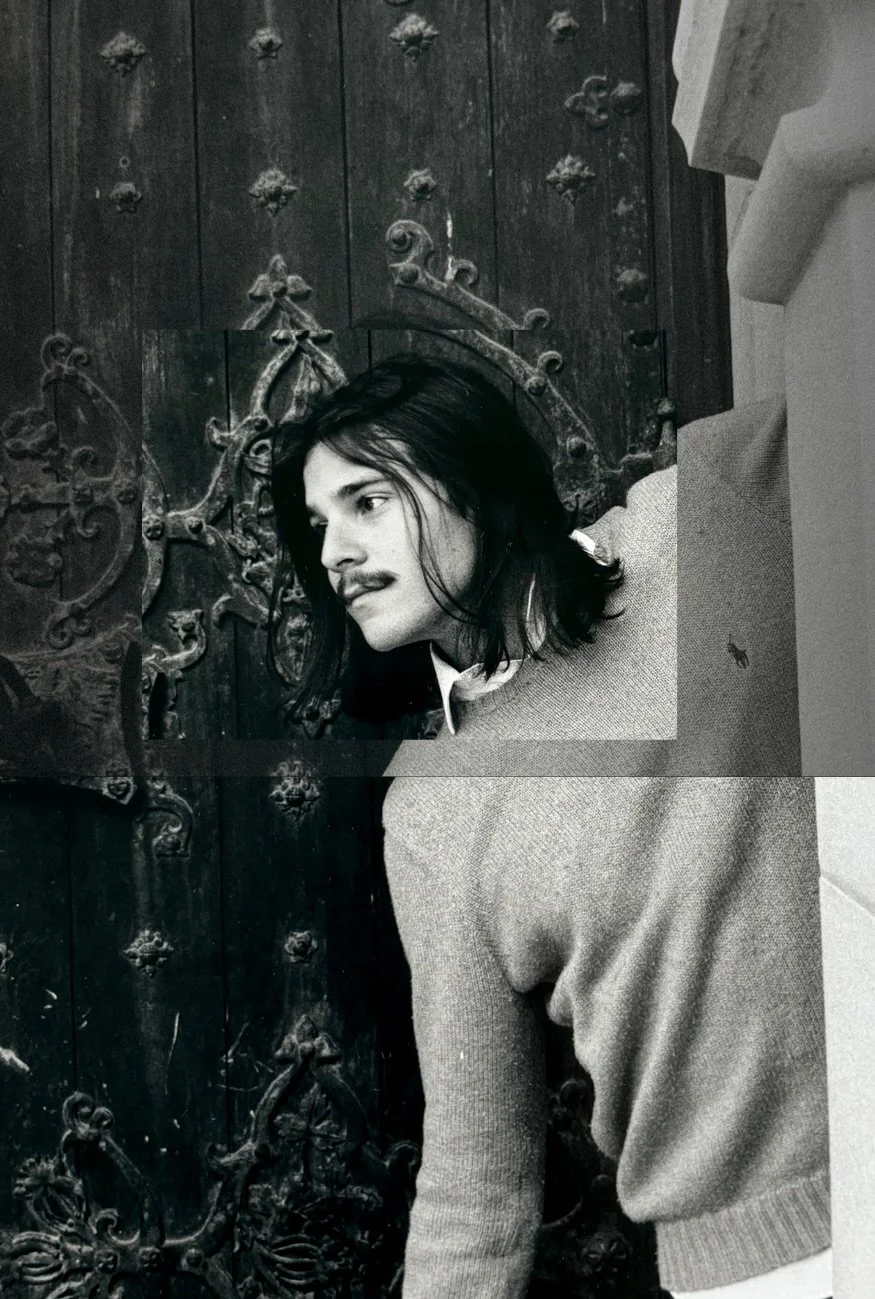

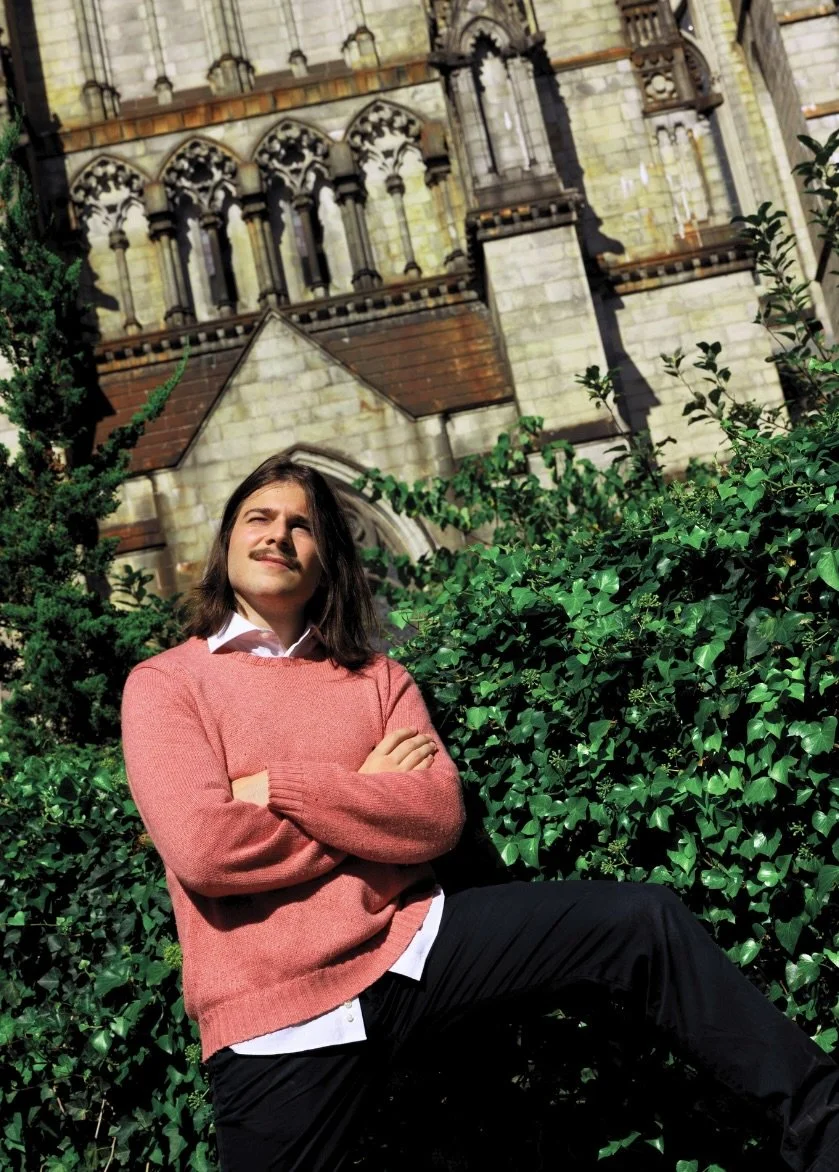

Photos by Yunah Kwon

Nicole Hur (GS ‘25) is an artist who seeks beauty and visual clarity. She is from Seoul, South Korea and is now based in New York City. As an English major doing the dual degree program with Trinity College and Columbia, she has continued to thoughtfully strengthen her poetic voice, photographic eye, and artistic work.

It is early on Tuesday morning, but campus is quiet–still absent of students as Fall Break comes to a close. I spot Nicole through the large windows of Barnard Hall, sitting in the gentle silence and typing thoughtfully on her computer. When she sees me she smiles brightly and stands to give me a hug, as we relish the opportunity to finally hang out outside our shared club meetings. While waiting for me, she confessed, she was writing a poem.

Together we walked to her dorm in the Union Theological Seminary. In the chill of the early fall day, shouldered by falling leaves and their signaling of a dwindling semester, we talked about grad school applications and MFAs, her love for her Senior Poetry seminar, and our shared time as Staff Editors on Quarto Literary Magazine. We get to her room, with novels and photography books overgrown on her desktop and shelves. I point out her huge pink Sofia Coppola Archive, and she shyly chimes in that she spontaneously got it at Coppola’s last-minute book signing–marveling at the suddenness and opportunity that we feel as students in New York City. As I sit at her desk overlooking the soft thrum of Broadway, she smiles, “Want to see the poem?”

In a soft and deliberate voice, she takes me through a mediation on materiality, femininity, and the ache of a dark space. As the poem is part of a private collection she is still working on and thus cannot yet be shared, I realize that I get to be a lucky few to see her at this crux of her art, right before it soars far beyond the university. It has stayed in my head since.

When asked to describe herself, Nicole chooses the all-encompassing label of “a creative person.” In all of her art, Nicole is exploring, and she urges you to explore alongside her. Her interdisciplinary work spans mediums of photography, filmmaking, visual arts, and writing. She tells me, however, that poetry is the thing that holds each of her artistic pursuits together. “Poetry has been the only thing that I have consistently done for my whole life,” she admits, as if the poetry is her longtime friend, or perhaps an innate, long-lasting spark that she is always carrying with her.

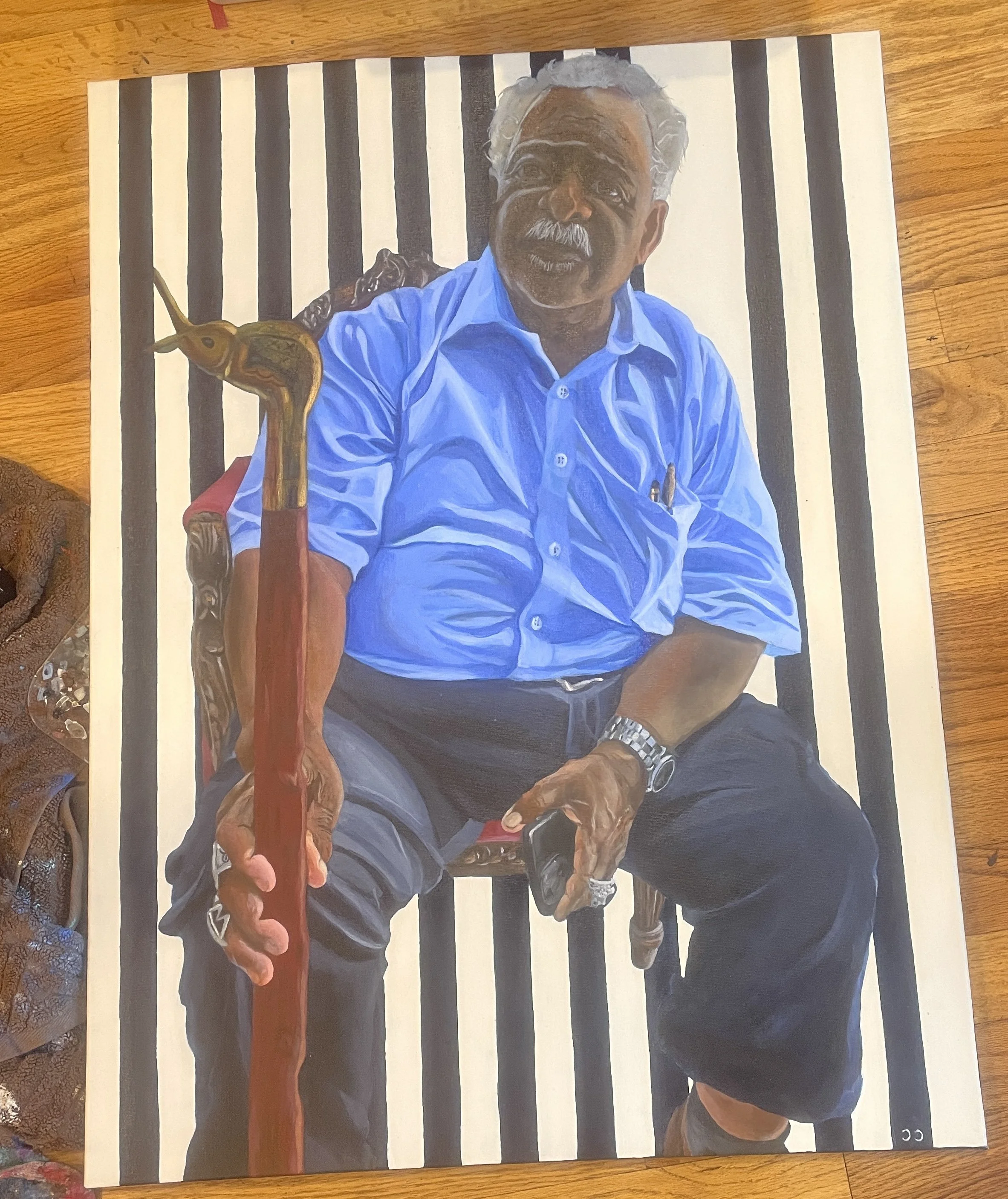

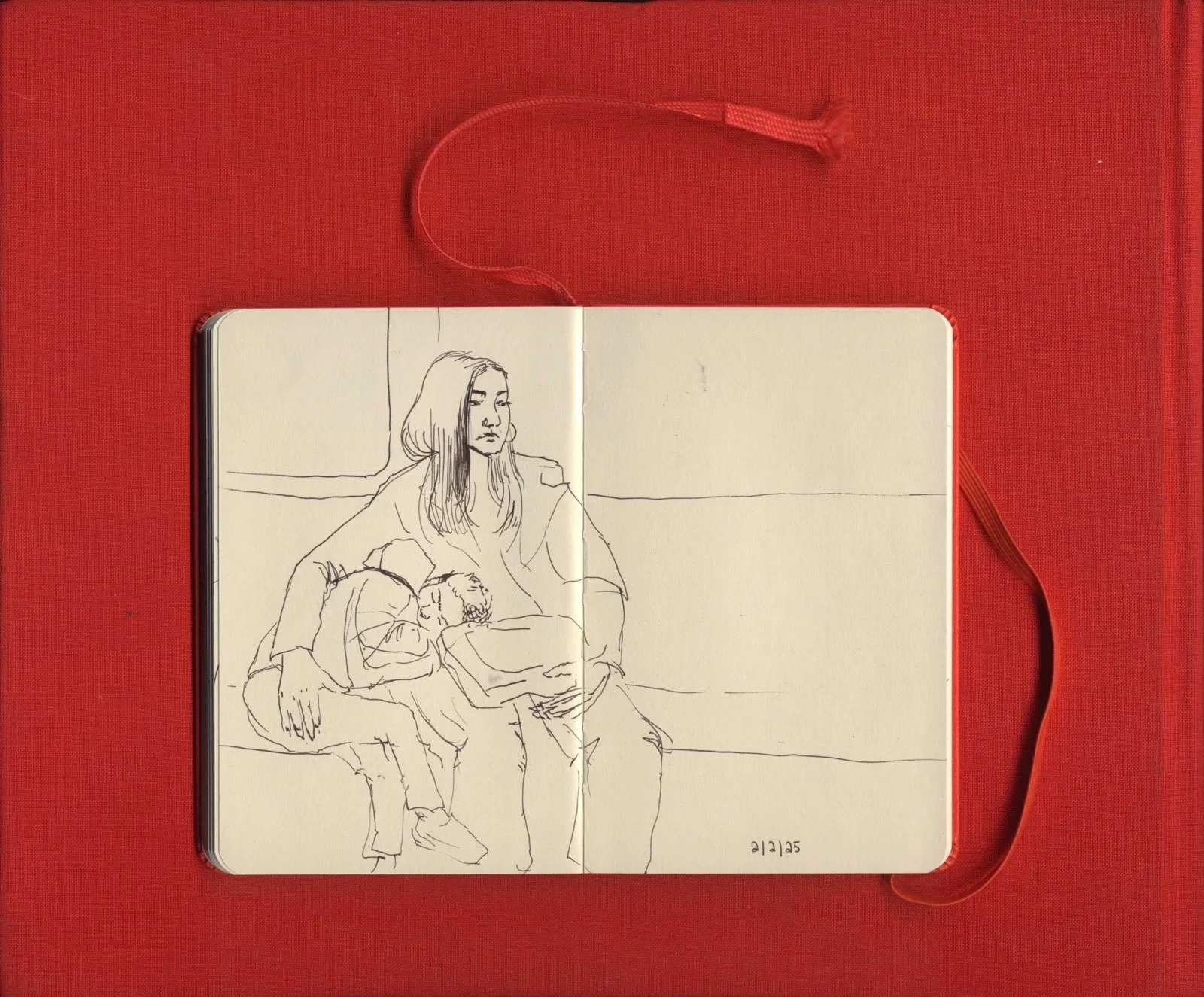

For Nicole, art is a visual practice. She hopes to create a lingering image or set a vivid scene—both in her poetry and her photography. It is evident how image-making is crucial to Nicole’s process and interpretation of her world. Nicole sees photography as “a place of on-site exploration.” She experiments with scene settings, the gaze of her subject, and how someone moves through a space. Juxtaposing her poetry process, in which she needs near-silence and a clear-head, photography is a medium in which she “just has fun.” She tells me about a recent collection she did in which she photographed her “very Korean grandparents” on a roadtrip to Arizona. One photo includes her grandparents sitting in a booth at an In-N-Out. She tells me the story of how her grandmother chastised her grandfather until he put on the In-N-Out hat, and how, as a result, their personalities brightly appear in the image—with her grandmother’s hat joyfully tilted and her grandfather’s perfectly posed above his quietly amused face. Here, she not only plays with the expectations of the audience but works towards capturing an incredibly special trip that brought her closer to her family.

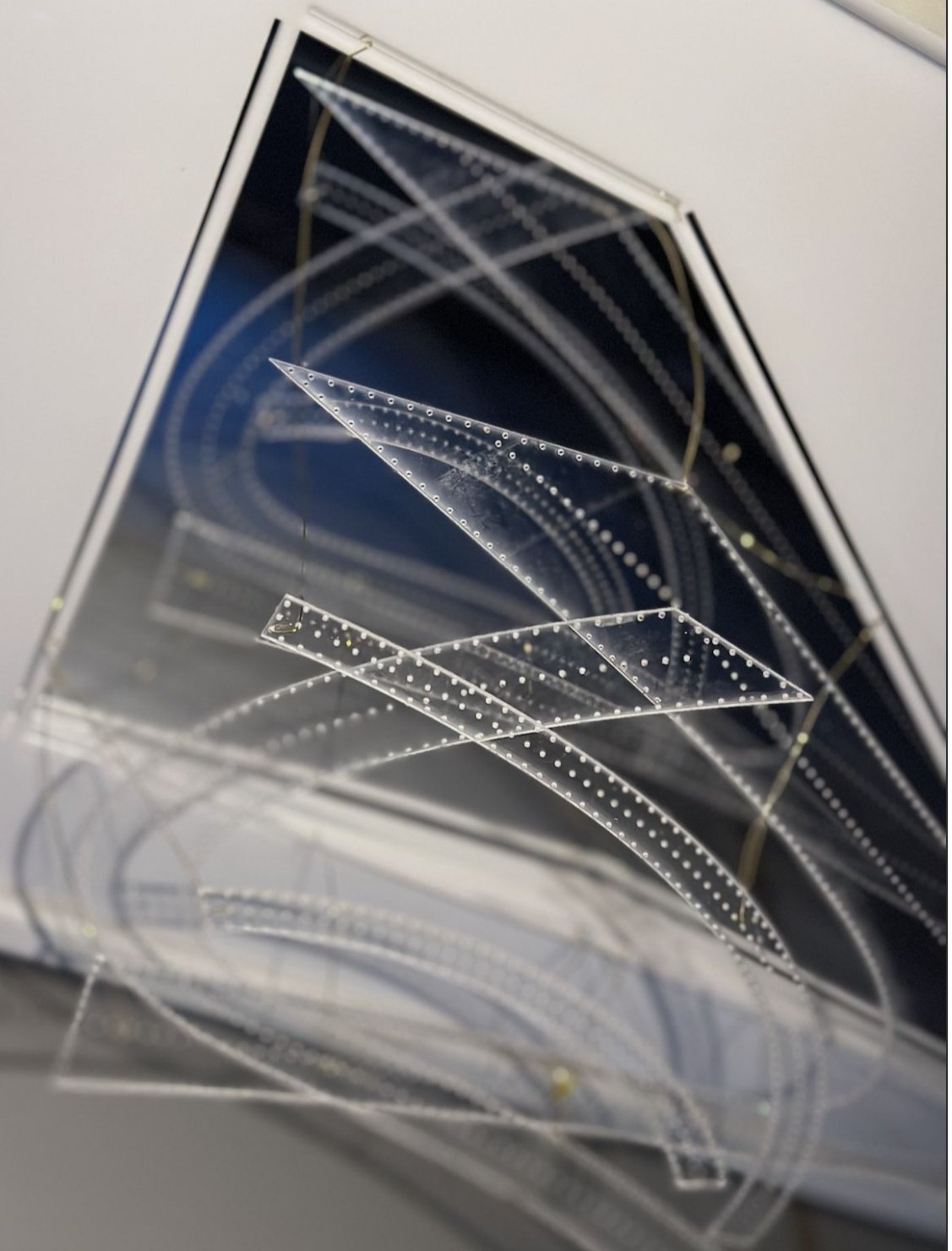

Nicole confesses that “every piece of creative work I have thought about has haunted me a little bit.” In a long notes app on her phone that collects each of these haunts, she makes art out of the pieces, slowly growing connective tissue around it. She tells me about two images in a MoMA exhibit by photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier, in which a black & white image of a hospital patient's back connected to a thick cord of wires splits a frame with an image of a demolished building, a mess of concrete, cables, and wires. In the shared space, ideas of vulnerability, desecration, and modernity are inextricably linked. For her, this is “what poetry feels like—two unrelated images, but something about them is speaking together.” Just like Frazier’s photographs, her poetry is an exploration that strikingly points out a hidden relationship between two opposing and seemingly separate sensations.

“What I love about poetry is how open-ended it can be,” Nicole tells me. “You can play with the shape of an emotion.” When I ask her about what she is focusing on now in her poetry, she speaks definitively: “It's about desire.”

In the open-ended space that a poem resides in, Nicole asks: what do we want? And why do we want it? Here, she contends with tenderness and grit, ephemerality and clarity, and always beauty.

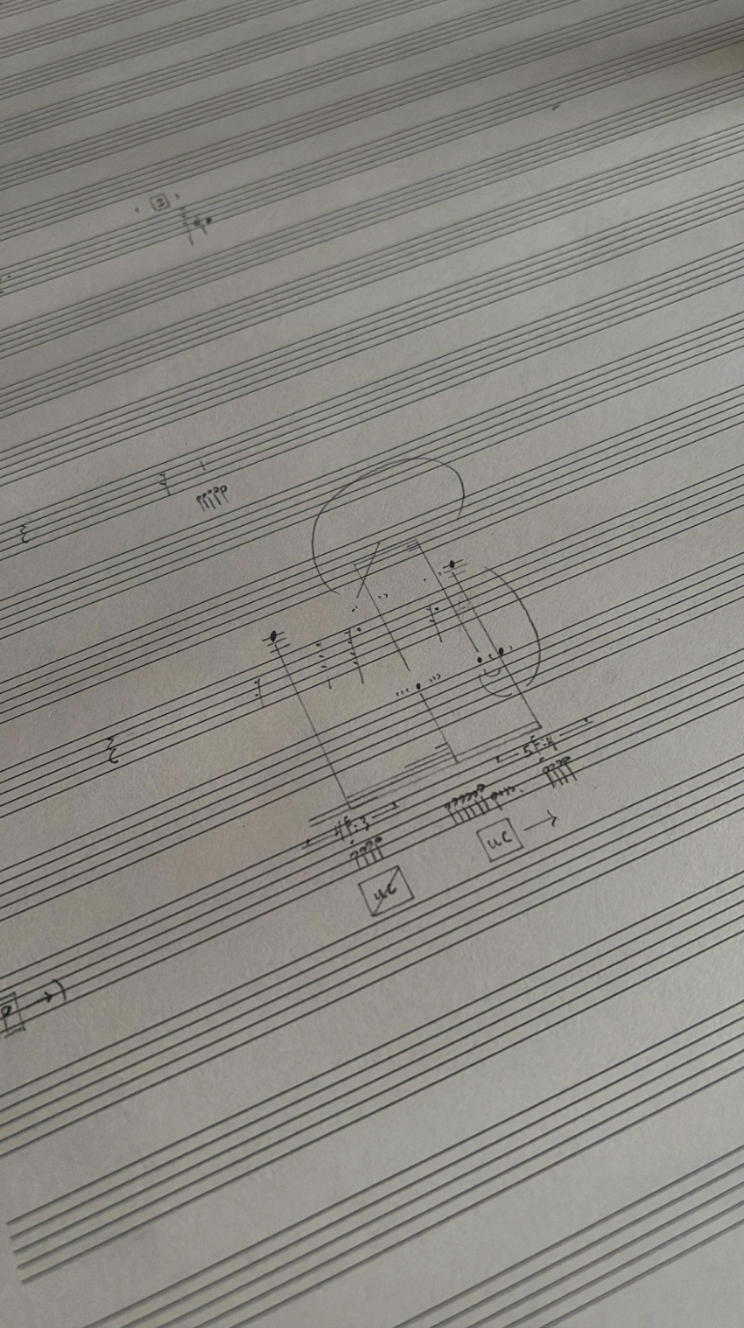

Nicole’s poetry is not only grounded in the visual, but in music as well. As a result of her upbringing with a violinist mother, musicality bleeds into Nicole’s art. In her poetry, she counts the beat of her words as if it's a sheet of music, seeing how it flows and is punctuated. Within this practice, the details are crucial, as Nicole explores how punctuation can invade the space of a poem or how leaving space can expand it. In the same way that a song can be quiet, loud, falling, or soaring, so is her poetry. Even though she jokes that she was always horrible at violin, Nicole’s deep sense of music and rhythm is potent in her approach to her work.

Nicole’s relationship to poetry has been strengthened through each of her artistic pursuits.

She is the editor-in-chief of The Hanok Review, a literary magazine that spotlights Korean poets and provides a space for their work to be translated to English-speaking audiences. In high school, Nicole discovered that her grandfather used to be the editor-in-chief of his university newspaper, and as a result, she realized her connection to Korean writers and her ability to make space for them. Freshly inspired, Nicole saw an opportunity to bridge her writing world in Korea with it in the U.S.—especially as she felt that there wasn’t a space for Korean translation outside of structured commissions. She thus worked to make translation more accessible.

Since beginning the magazine, Nicole has worked to break down barriers for Korean poets. She oversees translations, she reviews submissions, and she thoughtfully puts together an issue. “It can be really challenging,” she remembers, “I would be in my room with papers scattered all over, just looking at translations and organizing the issue.” Yet, she was never working alone. “I’m indebted to the team,” she expresses—which consisted of a mix of students, translators, and other published poets. “They were all really experienced,” she noted appreciatively, “and they had so much respect [for me] when I was young.”

In this work lies the unique difficulty of being a translator, especially from Korean to English. Nicole describes instances of not having direct translations or figuring out how to convey the same cultural nuances of a Korean poem in English. In some cases, she turns to poetic devices as a means to bring cultural definitions to a word. For example, if a Korean poem has a “feeling of being fluttery,” she looks to English punctuation to translate that sensation. She also plays with transliteration, using her position as a bilingual poet to bridge the different modes of thinking that each language provides her with. Through her translation work, her adoration for language and its exploratory power is evident. She expresses how a key element to translating is being a poet. It is not just her understanding of language that is necessary in translating, but also her understanding of form, shape, genre, and the emotion of a poem. The process is neither clean nor smooth, but Nicole embraces the difficulty. “If I'm going to do something,” she says, “I’m going to do it properly.”

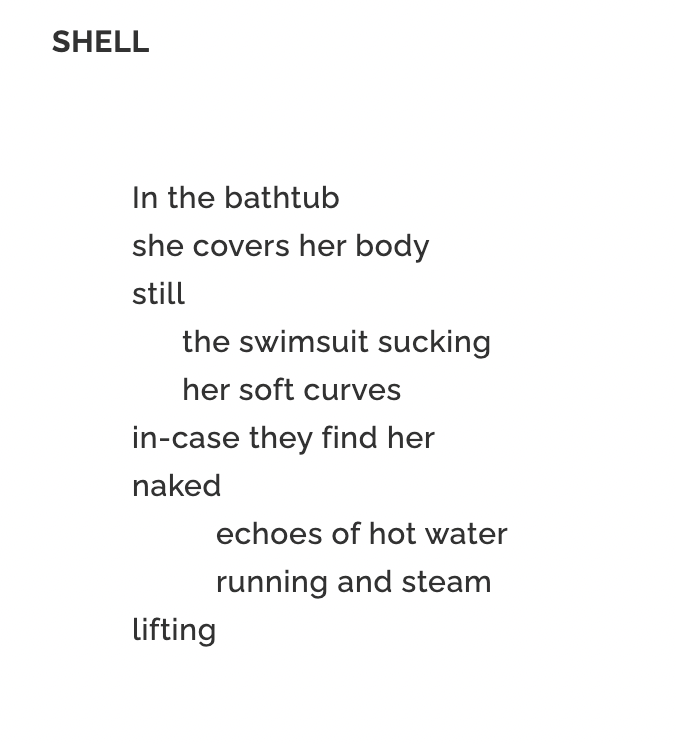

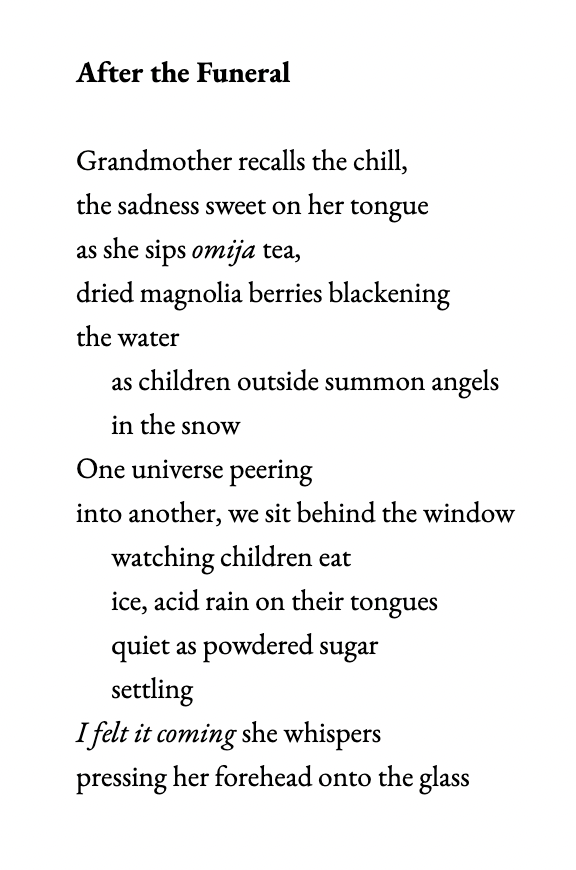

Nicole half-jokingly describes herself as “Korean-American-Korean”—a description that both poignantly highlights the liminal space she occupies as she straddles both of her worlds and reflects a larger sensation of the difficulties of categorization felt by many diasporic groups in the U.S. Yet, these worlds mold together beautifully in her work. She is deeply inspired by Korean writers and Asian-American literature, expressing,“I find a lot of Korean poems to be powerful because they're very simple, but emotionally, very impactful.” This manifests in her own work when she offers moments of brevity—either through form, structure, or a vivid visual image. I see this in her older pieces “Shell” (2021) published in Rogue Agent Journal and “After the Funeral,” (2021) originally published in The Poetry Society. In the latter, she poignantly paints a small moment of grief that still fully expresses its resulting sensation of disorientation, coldness, and solitude.

“Shell” (2021) and “After the Funeral” (2021)

As she balances writing ephemerally and directly, she ensures that her poetry is still connected by a striking image. “If I’m going to [write] something cerebral or loose, I want people to see it,” she explains, “It has to be visually clear.” She does not want someone to have a hard time reading her work or be left confused or frustrated. Instead, she chooses to be deliberate in the image she wants you to curate, and push you to ask questions around it. The right reader, she expresses, “is curious as to why you made a certain decision.” It is not always about making someone ‘get it’ but allowing for careful questioning. Nicole is incredibly conscious of the “mind-space a poem can take up when it's being read,” and that to ask for someone’s attention is a difficult task. She reveals to me that her work feels most indulgent when it is embracing this request for deep contemplation. She is hoping that, as she pulls you into an evocative scene, you feel an impetus to think.

As she reflects on her diverse mediums of work as an editor-in-chief, an arts and culture journalist, a photographer, and more, Nicole asserts that she is now purposeful in her focus on her writing. She warns against waiting for an opportunity for your work to shine, saying “That day never comes. You have to say, ‘I'm going to carve out time for my own work.’ If you want it, you have to do it.” Even in moments of halt, doubt, or confusion, “Nothing is wasted.” As Nicole works on exploring her voice and tailoring her work, she brightly expresses how she has only continued to see her writing improve. Every time she writes a poem that she believes is her best one, the next one is always better.