Interview by Sophie Paquette

Photos by Gillian Cohen on FaceTime

Introduce yourself.

My name is Raymond, I’m a sophomore from Northern California studying Visual Arts. A big part of my upbringing that influences how I perceive the world is my dual ethnicity being Chinese-Caucasian. Always having lived bridging two cultures, two ideologies, that’s reflected in everything I do. For me, the idea of an aquarium as a piece of fine art is similar in that you’re bridging these two disparate but linkable subjects. I see myself at the intersection of many different interests––I love cars, aquariums, art, animals, which intersect in surprising, odd ways.

I was thinking a lot about how, with the aquariums, you’re not only working with disparate media in the same piece but often fostering interaction between two structures, like two tanks communicating. Sculpture is obviously reliant on form and structure, and a lot of people see it as static. How does working with living media change the shape of your pieces? Does animal and plant life interact with your sculptures in a way that might surprise you or bring them new meaning?

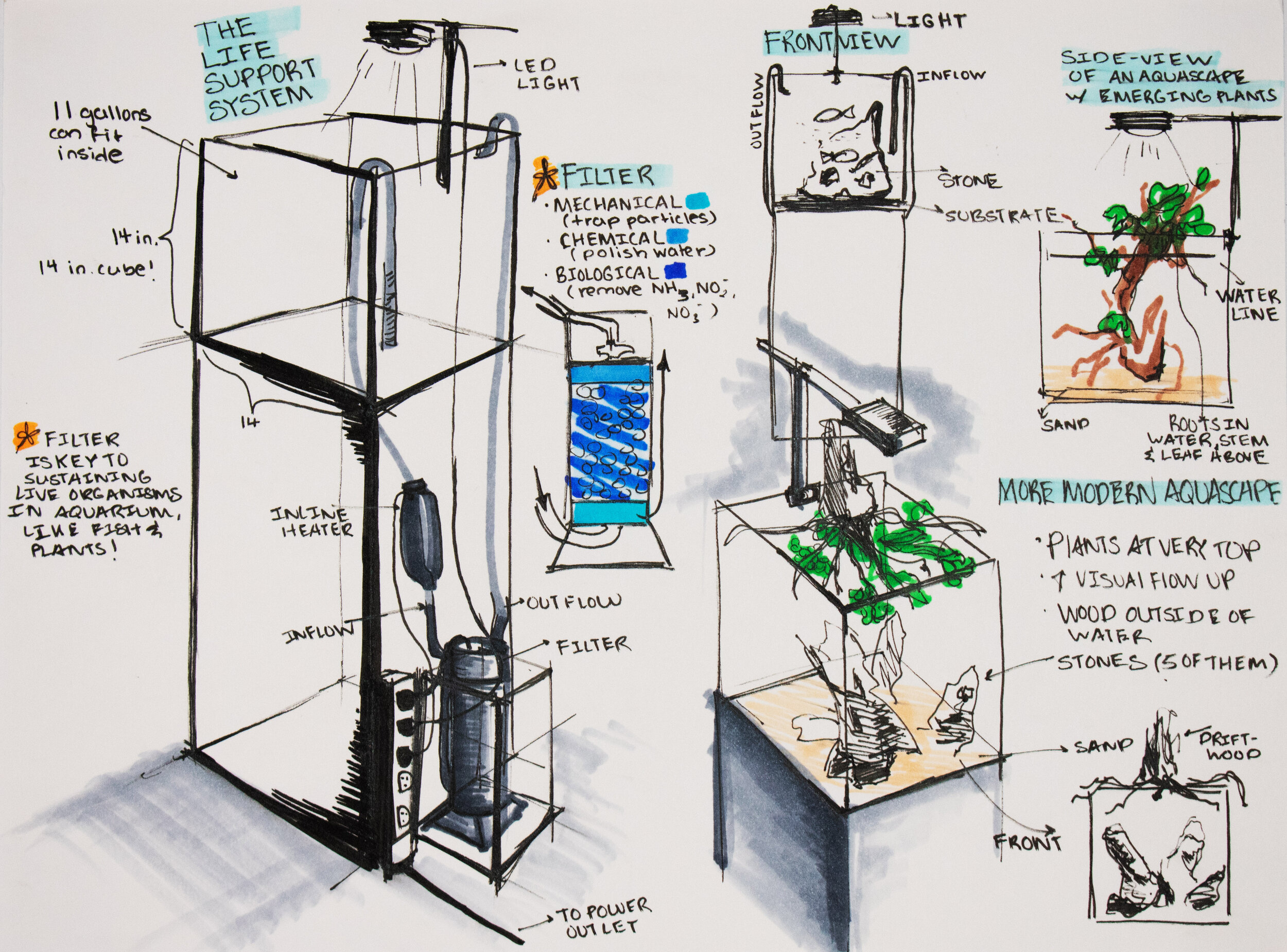

With the aquariums, I mainly took after Takashi Amano. He was kind of the father of the aquarium aquascaping practice. His whole thing is kind of like, “To know mother nature is to love her smallest creations,” paying attention to detail, to the smallest, more static forms and elements of life. A big part of his sculpture practice was not even putting that many fish but focusing on the environment, the plants, wood, and rocks.

It’s slow. It requires so much patience to really blossom. The labor of aquascaping isn’t in carving or chiseling, and it isn’t an additive process where you’re putting clay together; it’s a testament of time. Doing it for a couple of weeks is easy, but doing it to the point where the aquarium is stable for months? That’s the challenge of this art form.

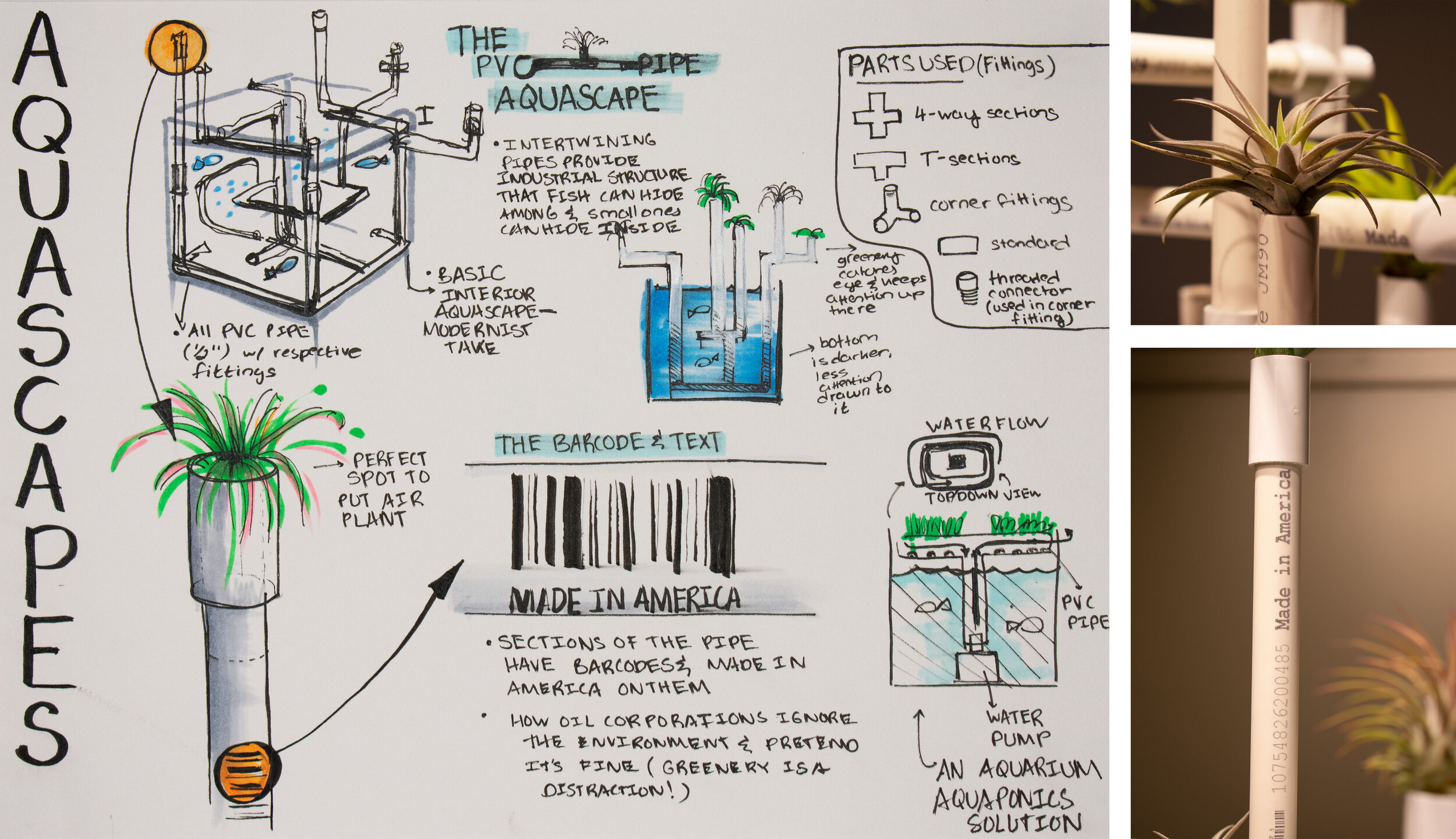

Made in America 2.0

I integrate artificial materials into my aquariums, things that we consider ugly, like PVC pipe, recycled beer bottles, and try to find aesthetic and material value in these manmade materials. Another part of the process is asking, what if I assign narrative to them too? That’s why a lot of my pieces discuss gentrification and issues pertaining to the climate. I see these living aquariums as models for social issues, stretching the boundaries of what materials are associated with. Not only can PVC pipes be aesthetically striking, but they can also tell a story.

I was really interested in how your sculptures personify mechanical media. I love this line from your website about Inter-Aquarium Conversation: “The installation ponders the notion of architectural spaces being able to converse with each other, depend on one another, and perhaps have a beer together!”

It’s making me think a lot about how, right now, we have to reconsider connection mechanically, digitally. We’re learning how to communicate intimacy without physical touch, asking how “inorganic” elements can connect.

There’s a technological and mechanical aspect to aquariums, not just with the filtration but with lighting. A lot of modern aquarium equipment can be controlled by your smartphone––it’s kind of crazy what you can do now. Aspects of technology, design, and biology all intersect so nicely with the aquarium. I like the aspect of working with elements developed by someone who isn’t really an “artist,” so when you return to the art world with more advanced equipment or a new rare species, you have a ton of confounding factors, you have unlimited choice, despite being framed within this glass box.

A Manifestation of Urban PVC in Terracotta Suburbia

But there’s also a big ethical responsibility as an artist working in this space, with living things like fish. These works can’t last forever, unfortunately, but I think that’s the most interesting part. You think of sculpture as being something that can pass the test of time––sculpture from antiquity has lasted so long. But a lot of contemporary work often uses found objects that won’t last forever, and then there’s kinetic work which definitely won’t because everything will eventually stop moving.

The difference between 3D and 2D art is this ability to view in the round. There is more to be learned than just looking at it from one angle, one plane. Modern sculpture adds the fourth dimension of time. You can look at my work from one plane, but the fish is going to be in a different position from one moment to the next. Eventually, it will decay.

There’s a performative aspect to it too––this is why I think performance art is fundamentally an extension of sculpture. I’ve always been very intrigued by performance; I used to do choir, sing, play piano, do debate… while they didn’t really stick I did love the performing aspect. There’s always this thrill you get from public performance: you’re making a point, a great expression for a short period of time; it’s fleeting.

Aquariums might be first interpreted as being all about containment, but a lot of your sculptures open up the space of the aquarium in really interesting ways. What do you see as the physical limits of a sculpture? What is interior, and what is exterior?

This is one of the things I thought about when creating sculptures with two aquariums. How much space can an aquarium occupy? Can an aquarium occupy space outside of its glass box? I think that’s where aquariums start to be considered art. It’s not just a nice design piece or something for the home, now it’s something that’s really interacting with installation. It’s unclear where it starts or ends spatially, and you’re enveloped in this space with multiple aquariums. How do you make an ecosystem not just for the fish but an entire ecosystem for humans to explore as well? How do various organic and live creatures take part in that ecosystem?

I don’t like the quiet or staticity of visual art as much as being able to make something that can draw people in, that captivates and enthralls. Moving water is fascinating to everyone––there’s a reason why aquariums are proven therapeutics. With aquariums, you don’t really need a proclamation as to why you should view it, because it’s already fascinating to watch it slowly change over time. There’s noise to it.

Terracotta Suburbia

When you first started talking about how aquariums are inherently temporary, it felt intuitive that, of course working in environmental media and thinking about ecology and the climate crisis, there is the immediate concern that we’re realizing our planet is not a certainty, and these natural things are not going to last forever.

But the more you spoke, it felt more hopeful, with the focus on how media can be repurposed and reborn. Opening up the space of the aquarium can have different implications on how we think about our natural world and our participation in it.

Right, and especially thinking about the pandemic, aquariums more than ever have become a way for people to engage with nature in a contained and safe way. While I don’t like the idea of mere containment, I do think there’s a benefit in that you have this beautiful slice of the ocean or the river, of nature, indoors where you can appreciate it.

Urban Overgrowth and Decay

Aquariums are also a great way to show people the value of biodiversity and the importance of protecting our ecosystem. You can view a lot of different species of plants or pieces of architecture in a miniature form, and then apply that to what’s happening in the macro world. I think of the aquarium as a smaller, more digestible package that makes the viewer think more critically about what's happening broadly in our environment at-large.

I’ve spent a lot of my life working in this field. I used to work at the Monterey Bay Aquarium as a volunteer guide and ambassador. A big part of it was just scientific interpretation, teaching people who have never seen the ocean about climate change, acidification, and why they should care about it. For me, communicating those ideas literally and scientifically is personable. You’re empathizing with issues in a way that makes them more digestible. Aquariums do that too.

A lot of outsiders criticize the ethics of the aquarium hobby; they’re like, you’re trying to harm our ecosystems, you’re harming these animals. And they have a point. They used to use cyanide to connect live saltwater fish in Australia. Fish caught by cyanide capture will most likely die or live a much shorter lifespan. It’s not sustainable for the consumer, and more importantly, it’s unethical. But I also think there is a huge awareness put into aquaculture. A vast majority of aquariums are captive-bred. There’s way less wild capture today than has happened in the past; most freshwater fish have been bred. There were fish we couldn’t dream of breeding ten years ago. The self-sustaining element of the aquarium makes us less dependent on nature while simultaneously allowing us to enjoy it more.

It’s going to be interesting to see the effect this has in the future, as environments degrade (or hopefully not), and as Covid-19 continues and people fear going outside. This might be too dystopian, but I can foresee a world where you see more species of a certain type in an aquarium than in the wild. I hope that’s not the case; I don’t want aquariums to be the only figment of nature that we have. But I still see them as being a valuable way to teach people about what’s happening in the world.

Lush Oasis

I’ve been thinking a lot recently about what it means for the image to not only replace but displace the original. That feels really crucial when you’re talking about species that are more populous in aquariums than the ocean or people whose first interaction with the ocean is an aquarium. Do you think the copy or reproduction is in some way equally “real” as the thing it’s replicating, or what different powers do they hold?

This was a big question for me last fall because YoungArts wanted to show one of my pieces in their Miami exhibition. They wanted the real thing in person, so for three months, the aquarium would be placed there. It’s a question of logistical setup but also asking, will this aquarium, in this location, be the same as the initial piece?

Every piece I make can’t be replicated. Artificial pieces might be replaced, but the fish won’t be the same, the placement won’t be the same… there’s no original that’s transportable. I think that’s kind of awesome because every time you make it it’s a new piece of art in a sense. There’s this idea that the original artwork will always have the highest value, but it’s not the same for aquarium-building. The real world inherently makes it such that every piece, every copy, is different than the original, but not necessarily better or worse.

It’s also interesting to think about this in the performing sense. With singing or acting, the performance won’t sound the same every time, but there are ways for you to improve every time, there is a certain aim for consistency. In visual art, though, you are performing and composing at the same time, and with my aquariums, a big part of the performance is spontaneity. How I put the PVC pipe structure for one exhibition or another is going to look different, because I make decisions based on how I feel about it at that moment.

I always feel for artists working in sculpture who have to document their work with photos, because that can be one of the most difficult forms to translate into a flattened plane. Especially working with living media, seeing your sculptures in real life must be a temporal, spatial, and sonic experience. So many things get lost when communicated as a still image. Have these competing boundaries of digital and physical space affected the way you define sculpture, form, and space?

I think there’s a great analogy to be made with the aquarium because, just like the Zoom screen, it’s a standard rectangle. It’s impossible to make a practical aquarium that is super huge or abstract in form. The aquarium, like every video interface, fundamentally exists in a box. The internet is a very rectangular, boxy media. It’s nice because I have a third dimension, which brings a wealth of exponentially greater possibilities compared to the two-dimensional computer screen. It’s a very comfortable restriction.

Untitled

Just like how I play with aquariums now, not just as a hobby but as an art form that takes up space outside the glass box, I can also Zoom people and play a game of Among Us with them simultaneously. The video has become a secondary way of expressing communication while you’re doing something else. The way you can interact with multiple people at once over video is kind of an extension or adaptation of one-on-one interactions.

I used to submit a lot of stills of my aquarium work. Initially, I saw aquariums as design-like, architectural. Now, they are much more about sculpture and installation, much more fine-art oriented. That’s one of the things I always liked about aquariums, how it creates these intersections of nontraditional media. It felt connected to my identity as biracial and having conflicting interests. Sotheby’s and the MoMA might make you think you need some kind of cultural knowledge to “understand” art, but I think ultimately, art is a way to visually express something personal. Good design and architecture, on the other hand, is invisible. Most humans know how to interact with and how to use good design because it’s intuitive, based on ecology, based on our inner nature. There’s not as much of a cultural barrier, if any, for design.

That’s where my work has been fluctuating around. It went from being a functional way for the public to learn more about ecology and enabling a home for fish and plants, to being more about expressing a certain personal viewpoint. It’s not merely functional; it’s representing something much greater than itself. Unlike an architectural model, which is made to represent an actual larger building, I think aquariums are models and art in and of themselves. You appreciate them for what they are, not just what they can represent.

Going from design to art has made replication harder. That, along with the spontaneity of working with live creatures and water, has made my work so much more dynamic, so much more difficult to document and to place in a certain setting, but that’s kind of the beautiful part about it too. That’s where I kind of think sculpture is heading, work that is a lot more fleeting.

On the topic of accessibility and performance, I feel like there’s something so crucial about the aquarium, as contained by transparent glass, being a space the viewer cannot and will not be able to enter. Unlike other installations, the aquarium space is not necessarily one you can participate in. Seeing how the art is operating and being forced to recognize your vantage point and the position of your body feels really important. With other sculptures, I’m not sure you think as much about where your body could participate in that piece.

I think installation and some modernist sculptures definitely changed how viewers interact with the work. Aquariums in one sense are very performative, but there some are also participatory. Touching a stingray at a petting pond––I mean, is that performance art, or is that just active viewership? Do the viewers become actors as well? At the very least, my work challenges what traditional viewership is. I want them to press their faces against the glass. I want them to be able to come close, to stare through the top of the aquarium, to hear what’s happening, to look at the hidden equipment running below. I want people to see all those living, mechanical, breathing parts, and take it all in.

What is the experience of moving from this embodied, physically participatory practice to digital media, which might feel divorced from the body?

Before I was making aquariums I was classically trained doing 2D work. The value in learning multiple media as an artist is not so much because you’re skilled, but it gives you more tools to express the ideas you have. That’s the value of knowing printmaking and painting, welding and woodworking.

I think now, I’ve probably grown most recently in terms of that transition into digital space. While I have been maintaining aquariums at home that are more traditional, I’ve been re-exploring what you can do with media. I got a much better understanding of Photoshop and InDesign, and some Illustrator too, over the summer and through this Barnard class Designing Design. So what I’ve been doing now is everything from making zines to graphic design pieces in Photoshop, really just pushing myself to learn these software tools to better express my ideas. Being at home has given me an opportunity to truly embrace digital media that I’ve always taken for granted. I think I started taking digital media seriously when I first learned photography to document my sculptural work and my paintings. I learned photography in the first place, and then it became creative as I got better at it, better at documenting my things.

But there is a huge limit, like I said with aquariums, when you have to document them digitally. It’s a wholly immersive experience but with photos, there’s no audio, there’s no kinetics, you can only view it from a few certain angles you choose. The view is so much more restricted. That’s the trickiest part, I don’t know in the near future what presenting aquariums will look like. It’s not something I’m worried about, but digital media definitely alters a big part of what it means to be a sculptor.

Infinite Flow

Over the summer, I taught an art portfolio camp for teens over Zoom. Portfolios have always been submitted digitally, but over Zoom, even I couldn’t see their work in person; it was like I was always viewing it in the way a reviewer would. Going digital definitely trains artists to think hard, to think outside of themselves, to be the judge and the creator. Especially during this digital media era, you have to view your work outside of yourself. Work is always going to be processed in a two-dimensional way, so knowing how to present it will help improve the quality of your 3D work too. That’s definitely been something big for me.

What are you looking forward to, artistic or otherwise?

I’m moving back to New York in the spring which is really exciting. I hope there’s an art class I can take in-person. I want to get back in the habit of creating––especially going to a school like Columbia, where you’re so academically busy. Even if I do a Zoom drawing class, that’s definitely going to be great, just to sit down and draw. Yeah, pragmatically you get a class done. But it’s also really nice to have a structured environment to do that in. For me that’s something I’m looking forward to more, I haven’t had that in a while, I’ve only taken two art classes at Columbia so far, and one design class.

But I’m interested in working more on visual projects, infographics, photos. There’s so much opportunity that’s untapped in the journalism space. That’s probably my big Spectator project, which ties into digital media and work too. How do we optimize what an illustrator can do, for more than just like a mere illustration for an article, you know? Maybe I’ll even get into more advertising and marketing––I’ve always been fascinated by creative marketing. Because I haven’t been able to produce as much fine art as I would like, I’m seeking other avenues to apply art. That really excites me. I think that’s the next step for me; applying my art and curatorial work to journalism or business is something that I do want to pursue more of in the future.