Feature by Stuart Beal

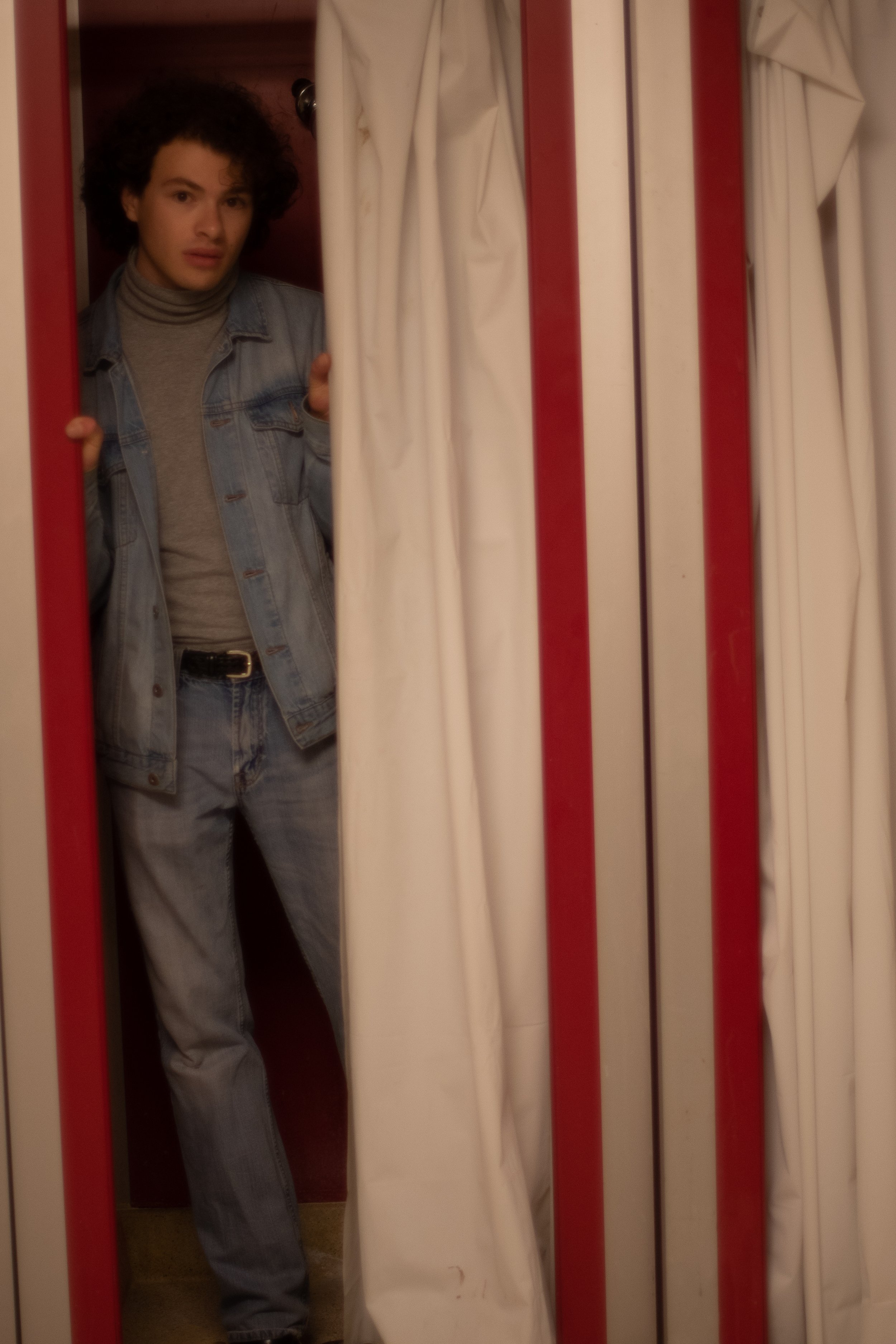

Photos by Adela Schwartz

Warren McCombs is a senior visual-arts major from Greenland, Arkansas, who makes sculptures and performance art. We met twice, discussing his current and past work, New York City, and home.

We approach Schermerhorn and it’s raining.

I say that I hope the building is open, not because I don’t want to pick another location for the interview, or because I don’t want to be out in the rain, but because sometimes, when you first meet someone, you make inane comments to fill the empty space–or at least I do.

He responds immediately, saying that Schermerhorn is open 24/7.

And so there I am, tapping my ID and opening the door, not five minutes after meeting him for the first time, imagining him walking through the hallways of Schermerhorn in the middle of the night, probably in elaborate footwear: cowboy boots, heels; he dresses extravagantly, and well.

The first thing I learn about Warren McCombs is that he is the type of person to wander around buildings late at night, keeping track of which ones will allow him such a pleasure, and which won’t.

The last thing I learn about Warren McCombs involves an 1,800-pound block of concrete on furniture dollies barreling down a steep section of Broadway.

Warren McCombs is a senior visual-arts major from Greenland, Arkansas. It’s a town defined by proximity, just outside of Fayetteville. I feel a sense of kinship with him, being from a small town in Texas myself, and when I ask him what the South means to him, how he relates to it, if he relates to it at all, he answers simply: “I like where I'm from a whole hell of a lot better than I like here.”

To the extent that these words sound negative, they aren’t. Or, maybe they are, but not in the way that they seem. McCombs doesn’t hate things for the sport of it. When I try to relate to him by bringing up the cattiness that sometimes seeks to define creative writing workshops, and that I thought would be similarly present in visual arts workshops, he doesn’t take the bait. “I don't think I've ever talked shit about somebody's art behind their back.” I certainly can’t say the same.

This type of honesty defines the conversations I have with him. When you speak to him, he pays attention. And when he speaks to you, there is no sheen of performance or presentation. I’m sure many artists have claimed to have never said something cruel about another person’s art. I’m also sure many of them were lying, in the same way I’m sure that McCombs isn’t.

His main reason for preferring Arkansas over New York City: space. Artmaking is a very physical experience for him, requiring him to pace and move around a lot, and he feels like he can’t do that here.

Despite this constraint, being in New York City has influenced his work. The most formative piece of art he’s made during his time at Columbia is "Oh my goodness, my brother, are you gonna be alright?", a performance piece in which McCombs recorded a time-lapse of himself walking the entire length of Broadway barefoot, taking 5 hours to cover the 14 miles. The project, which started as a test of his endurance, ended with a focus on how others reacted to him. The only person on the street that said a word to him was Cornel West, who happened to be walking by.

“He gestures to my feet, and he says, ‘Oh, my goodness, my brother. Are you going to be alright?’ And he puts his hand on my shoulder and I’m like, ‘Yeah, I'll be fine. I'll be fine. Thank you so much.’”

Another piece he made while at Columbia is entitled “Wunderkammer,” which translates from German to “cabinet of curiosities.” Besides the plywood receptacle, the sculpture is made entirely of objects McCombs found on the street during a single walk through Harlem: a brass handle, food scraps, an old metal washer.

Still, if I was tasked with making a list of things that might be occupying his mind during his late-night jaunts around campus buildings, New York would make the list, along with the prospect of him leaving it.

He’s looking forward to graduation. He has a slight Arkansas accent, and he’s afraid of losing it. I was nervous going into the interview. Within minutes, I wasn’t anymore. If he saw someone else walking barefoot down Broadway, I have complete confidence that he would stop. He spoke carefully throughout our conversations, letting the silence hang, which I quickly got used to. He was especially well-spoken when it came to New York City, communicating a sentiment I know I’ve felt being here, and that I suspect many others have felt too.

“When it’s cold, it feels hot here, and even when it’s quiet here, it still feels loud. It's like the people are just making it feel like a way that it isn't. I don't know. I don't know how to describe it. I feel like I've never been cold here.”

One of the sculptures he’s working on right now has a concrete base that he’s embedded dumbbells and a metal rod into. From this metal rod hangs a microwave.

Another current project of his is a sculpture that attempts to deceive the viewer. He constructed a scale and plans to put something that appears to be very heavy on one side and something that appears to be very light on the other, but have them balance each other by hiding weights in the side of the scale holding the lighter object.

McCombs doesn’t have explanations for why he makes the things he makes.

“When we do critiques, people will ask, what are you trying to do with this? What made you want to do this? And I mean, much to the frustration of many of my professors, I always answer, ‘I don't know.’ It often gets a laugh, but then I'm like, no, I'm serious. I really don't know.”

For McCombs, this intrinsic, unexplainable desire to make art operates differently in Arkansas than it does in New York City. In New York, he finds himself being slightly more avoidant, turning away from certain emotions or fears.

“I feel so much more free to make anything in Arkansas for some reason and I don't know why.”

The project he’s most proud of dates back to Arkansas. It’s a sculpture called “Scrap,” the second sculpture he ever made. It’s a stack of ten or eleven miniature cars he made, each representative of a car that played some role in his life.

“It’s sort of this homage to a childhood in an area around so much junk, and so many junk vehicles, in particular.”

During our conversations, the brightest details he gives are the ones from Arkansas. He grows watermelons in his backyard every summer, massive ones. He spent time as a kid trying to break obscure world records and claims he did break the record for the highest unsupported stack of pennies, but never got it certified.

One of my friends once said she thinks all artists are nostalgic. I think she’s right. I also think that nostalgia is a kind of wandering, a wandering that everyone needs to do in order to be alive, but a wandering that few people have the guts for.

At the top of the previously mentioned list of things I think McCombs might be thinking about while walking down Schermerhorn hallways in the middle of the night: Arkansas.

In October, a massive chunk of concrete broke off the Columbia Law School building, Jerome L. Green Hall, and was placed in front of Wien. McCombs considered trying to move it and do something with it, but he hesitated. Eventually, the university took it somewhere else. What held him back were his concerns about what could go wrong if he tried to transport it.

“You got an 1800 pound block of concrete on some furniture dollies and say you're kind of taking it down a steeper part of the street and it starts rolling a lot faster than you think it might. All of a sudden, you know, it's like smashing into a car or something…”

This anecdote captures what it felt like hearing Warren talk about Arkansas and New York City. He’s in this city with a massive thing in his hands–his life, Arkansas–and it has the capacity to so easily get away from him and create something dangerous–a version of him who disregards where he’s from, who’s perpetually unmoored, pastless.

I think letting go is, in some ways, inevitable. But I think a lot of people give up before they should. And I think nostalgia is a surefire way to hold on tight.

McCombs has a much stronger hold than most.