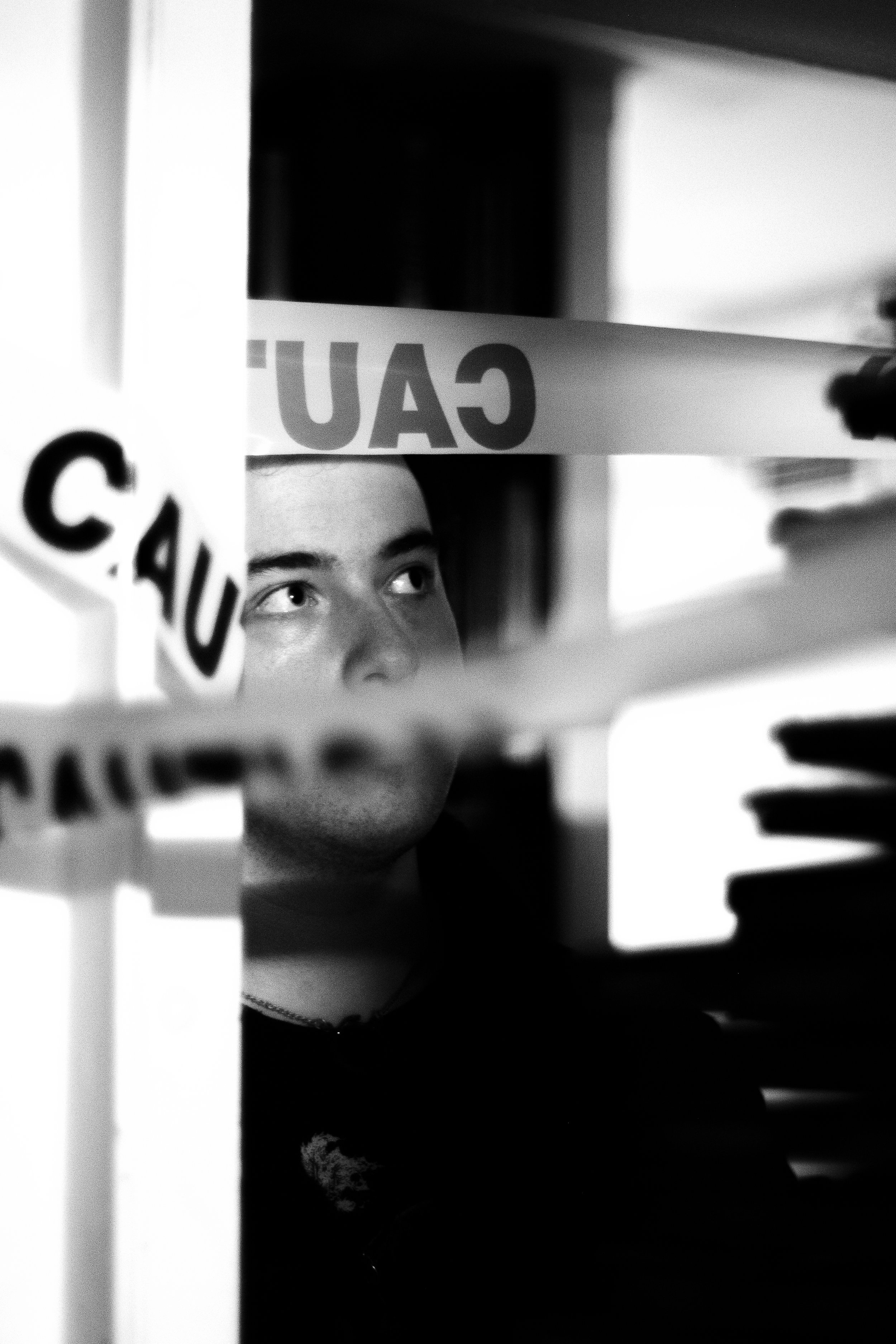

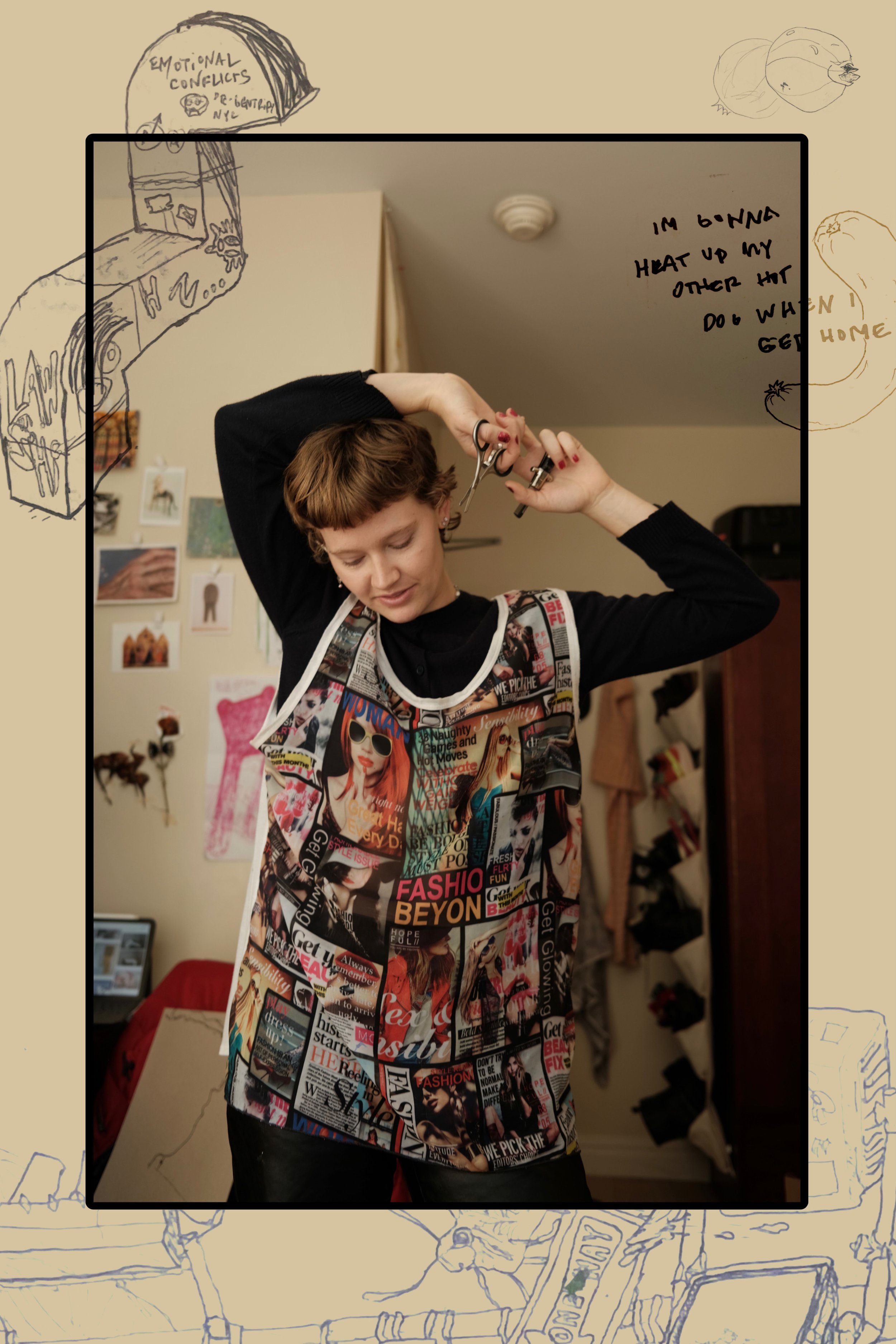

Feature by Claire Killian

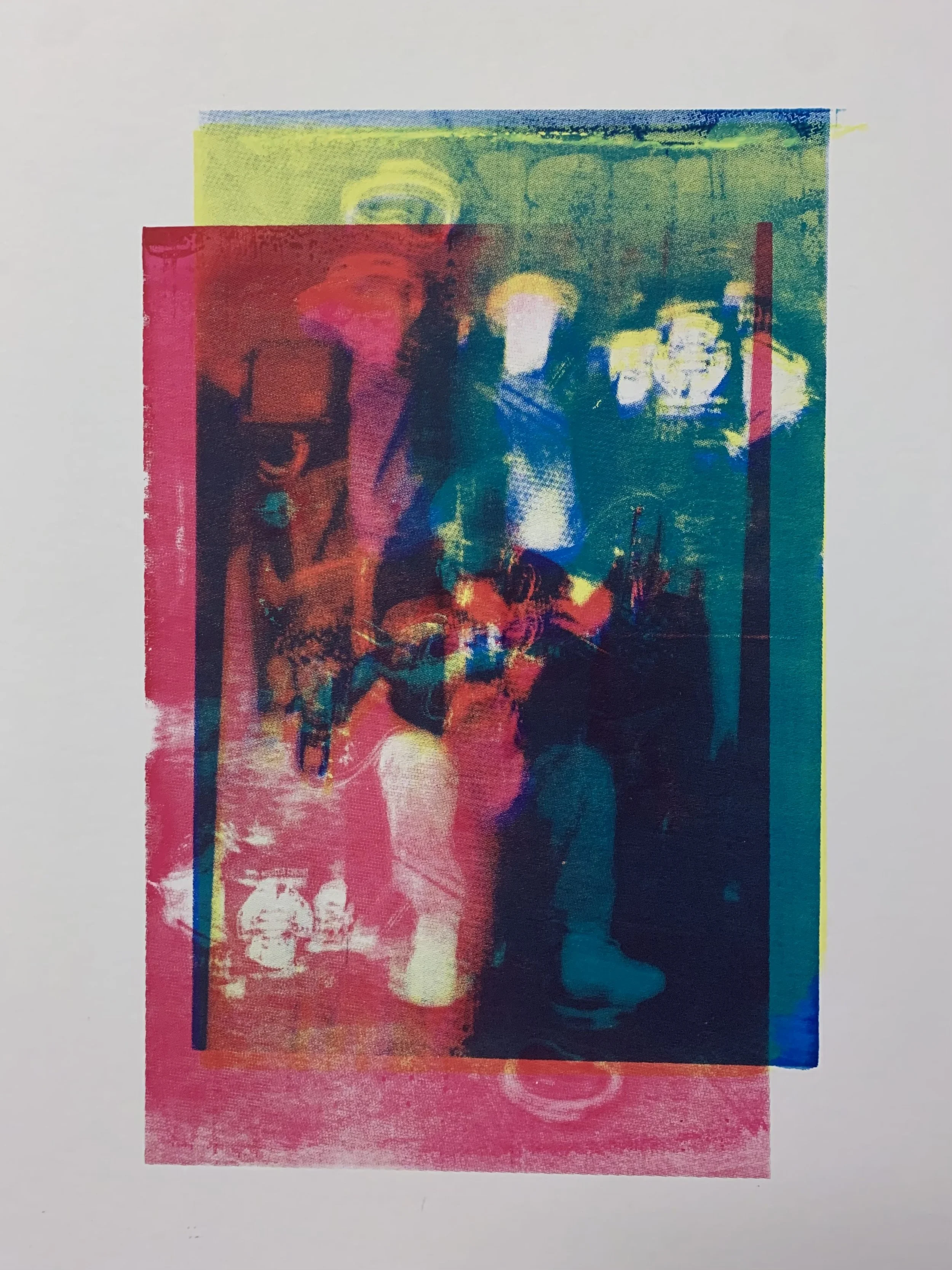

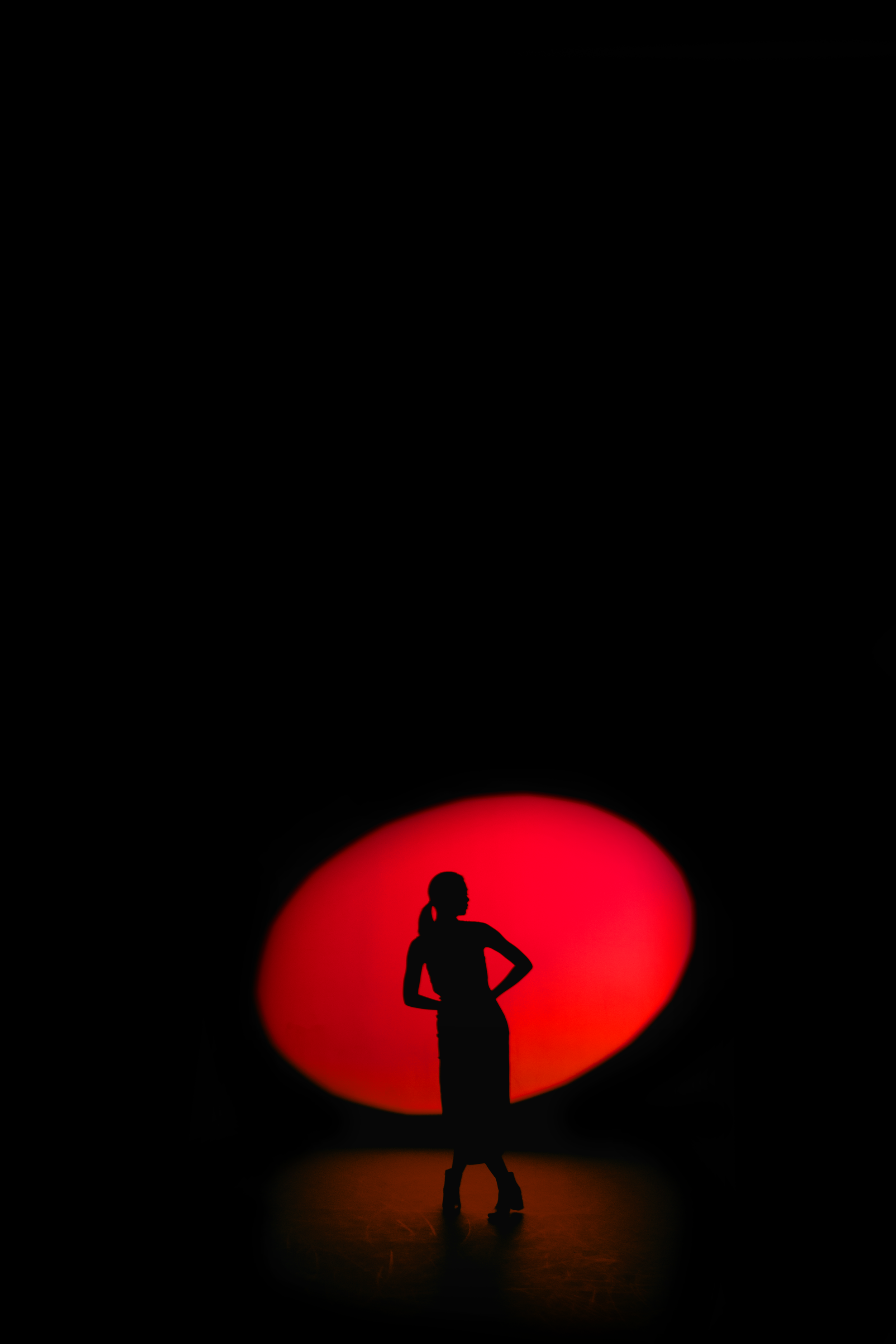

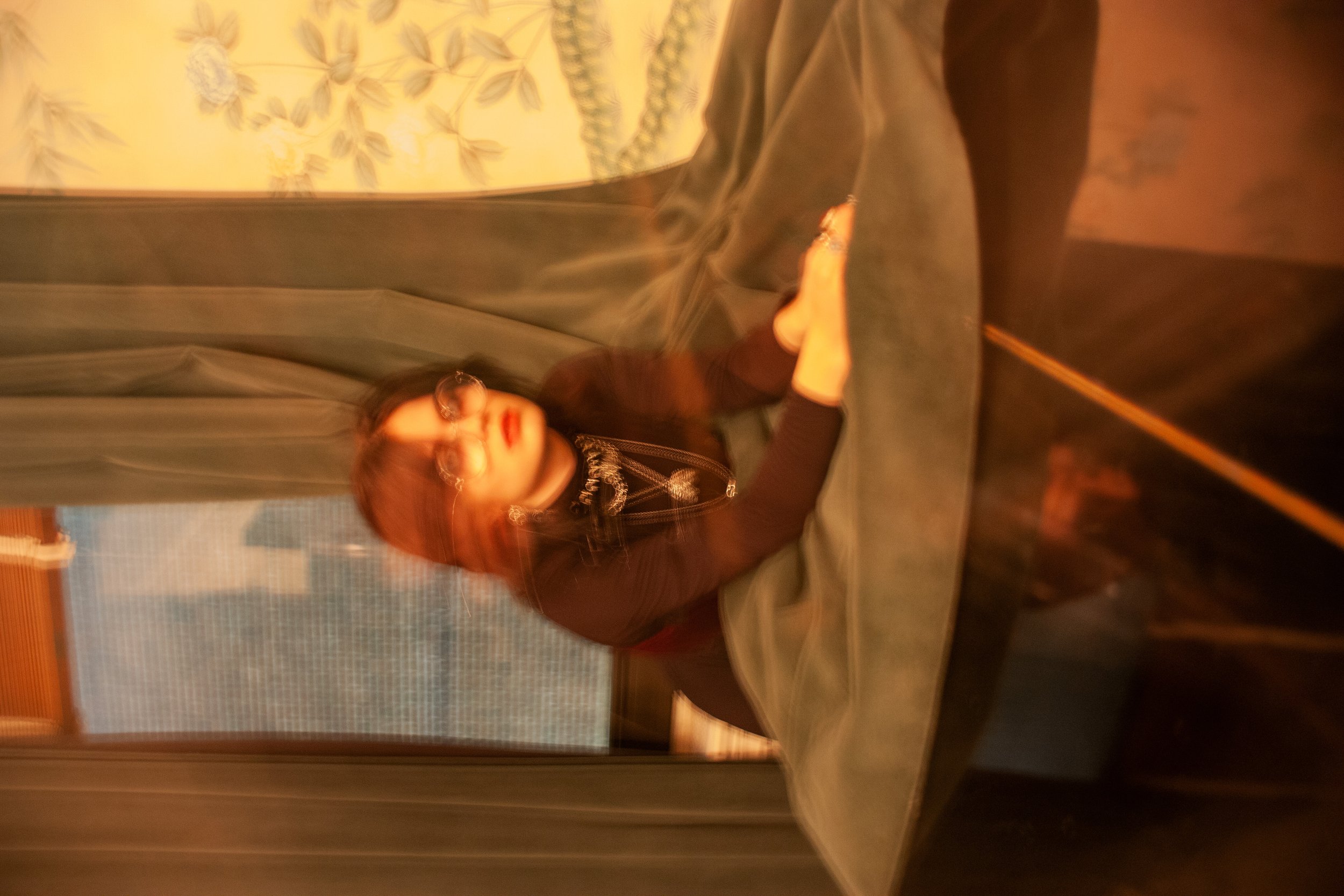

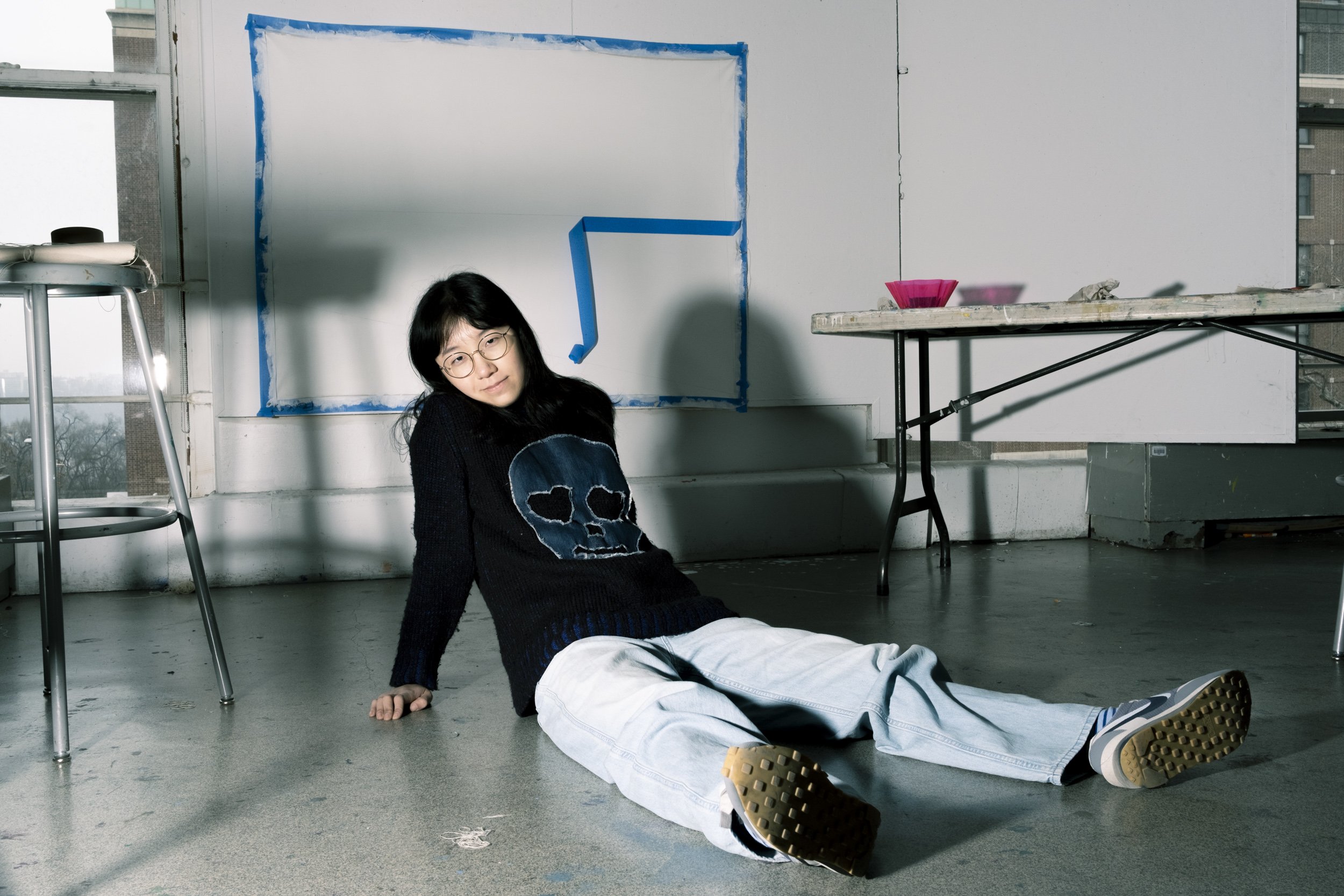

Photos by Anushka Khetawat

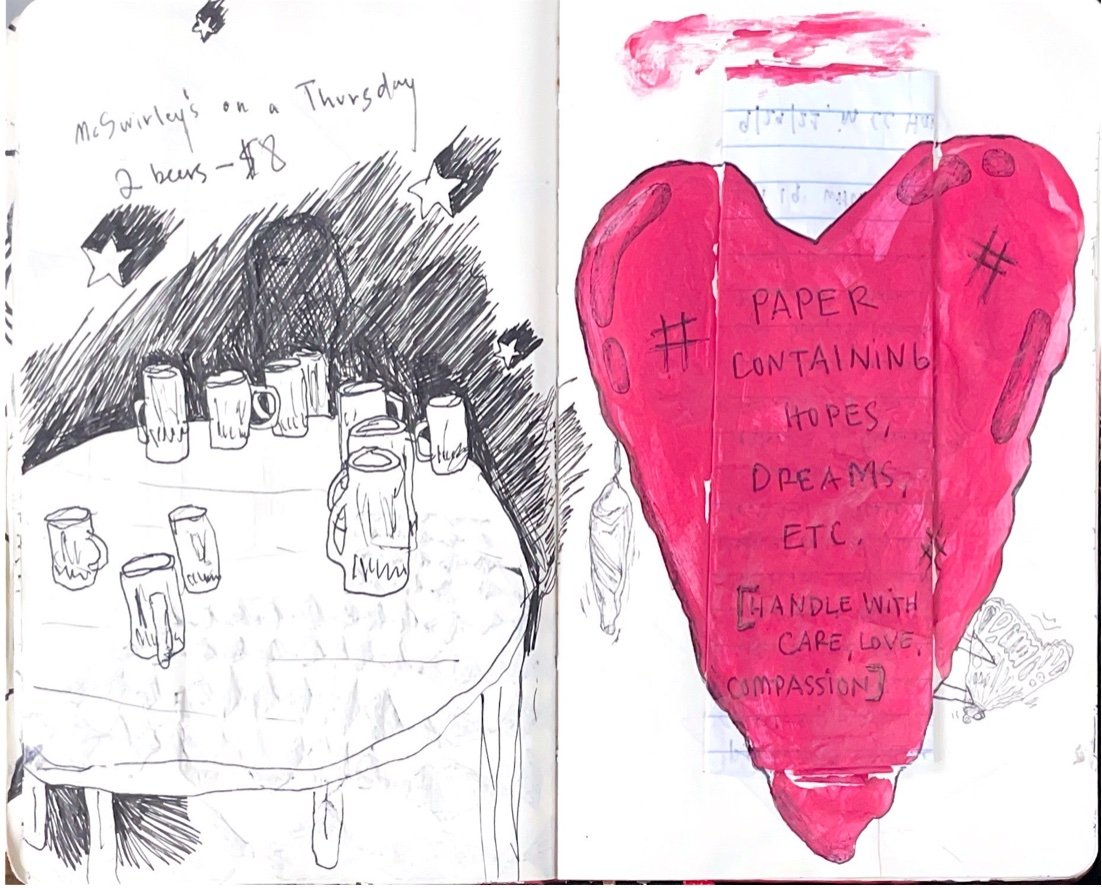

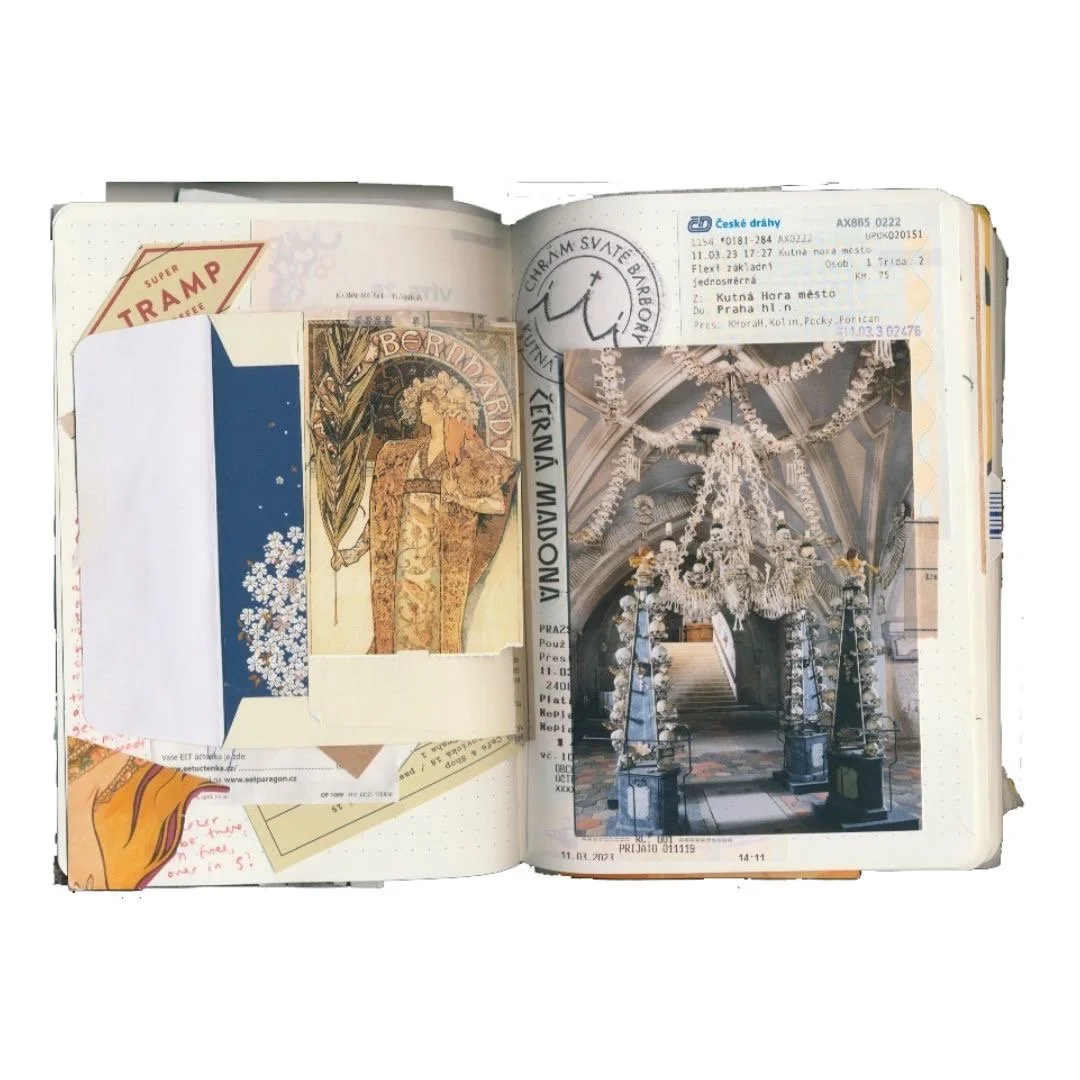

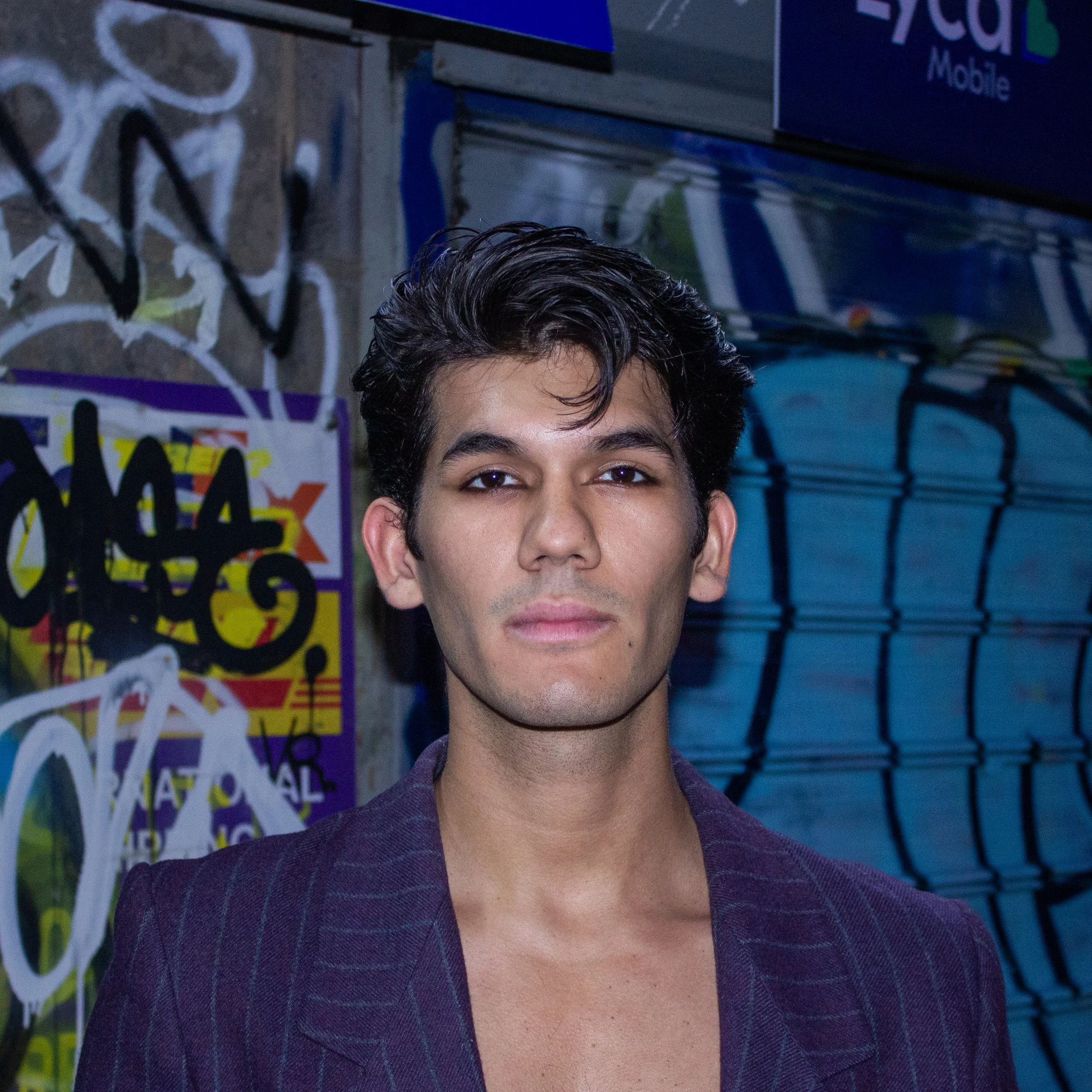

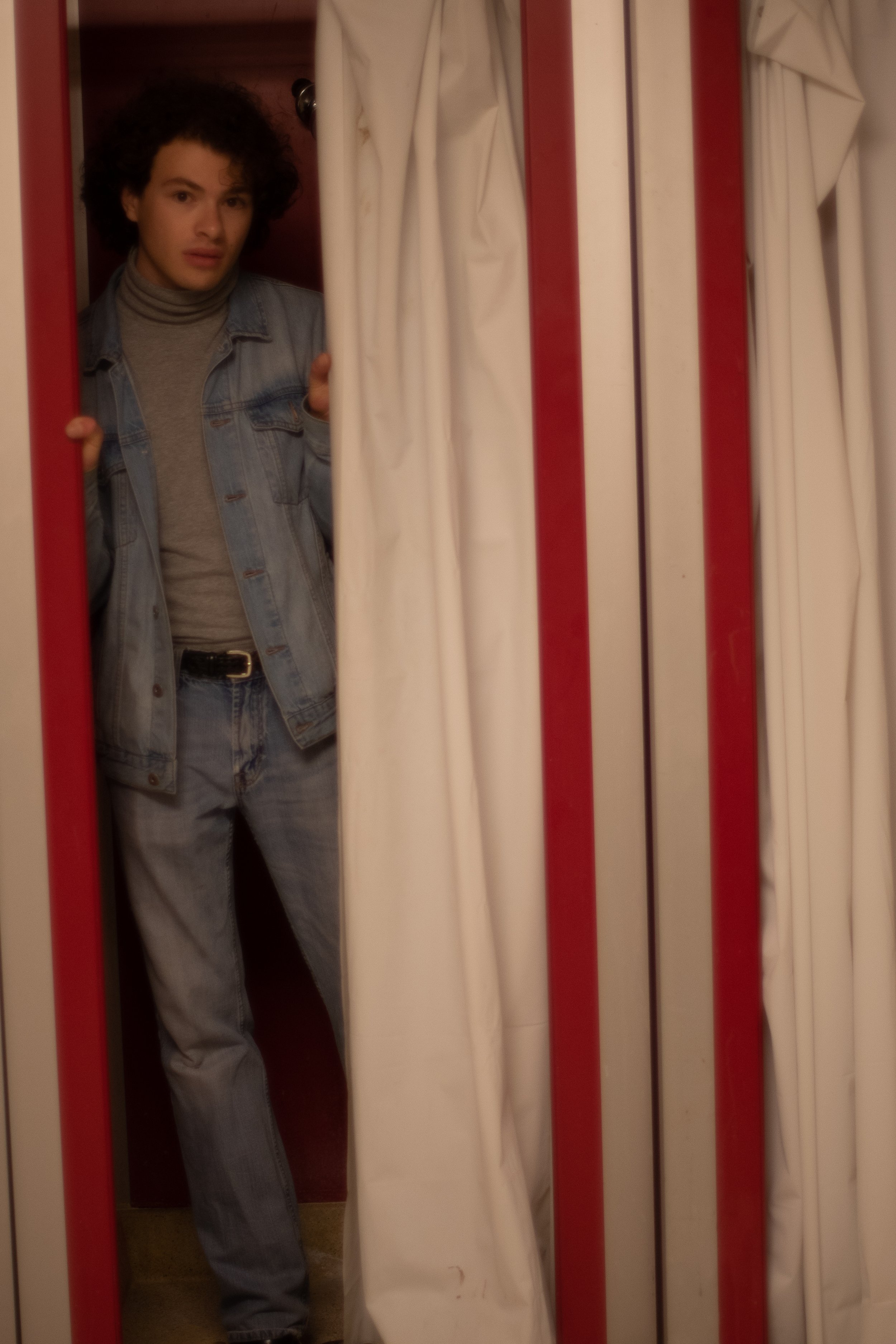

She may not have realized it, but in her black turtleneck and leather jacket, Sofía Trujillo looked every bit like the writer I had imagined. With my hair pragmatically pulled back and my notebook and pen in hand, I probably looked exactly like the interviewer I was playing at, too. I had suggested we meet in Butler to chat, which she countered with the Hungarian Pastry Shop – an infinitely better choice given the shop’s ambiance, and its deep roots of literary history. We both waved to friendly faces (a few we had in common!) as we shuffled awkwardly past the tight tables, to the back, and sat down. I was waiting for my first almond horn of the season, and she had a hot chocolate coming.

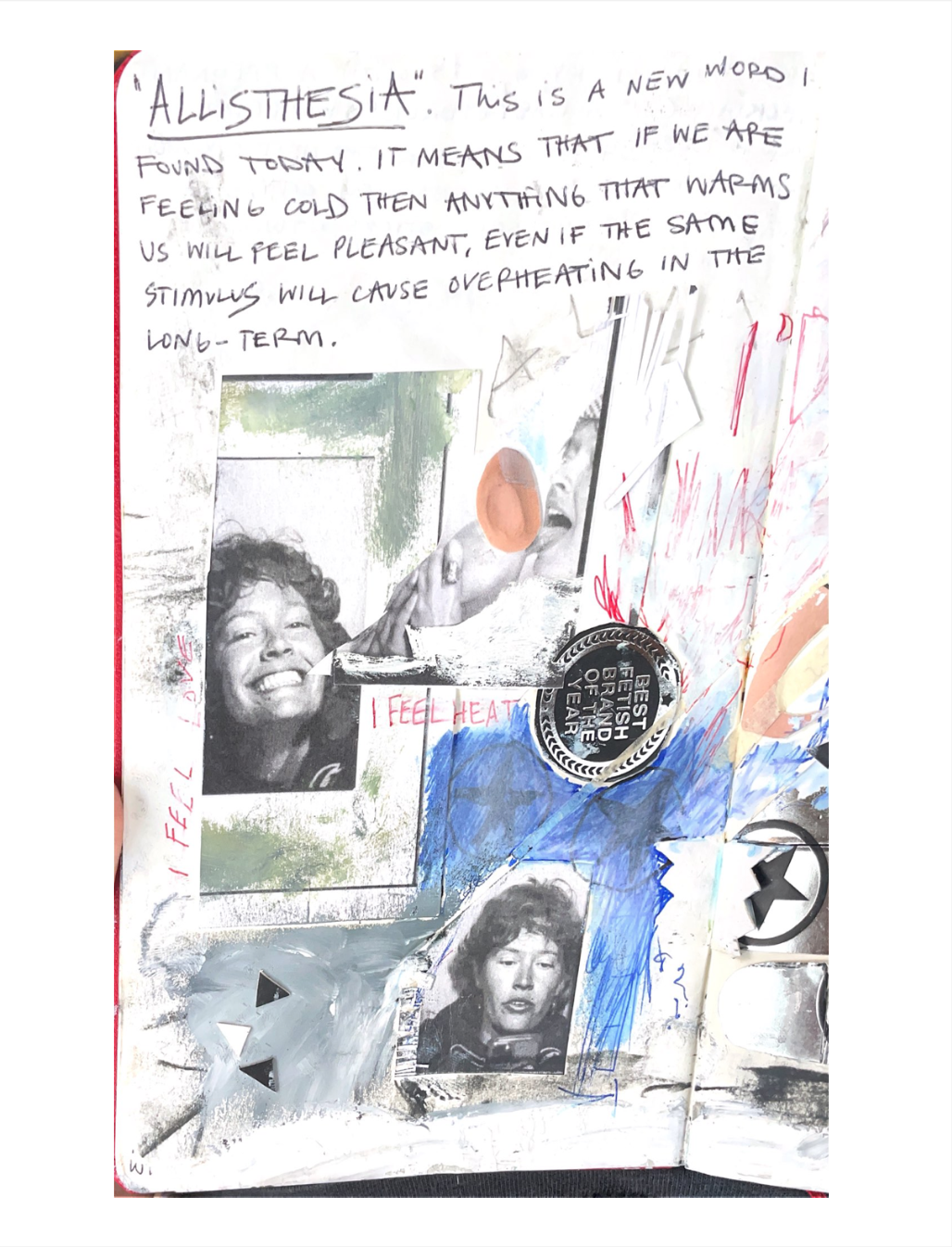

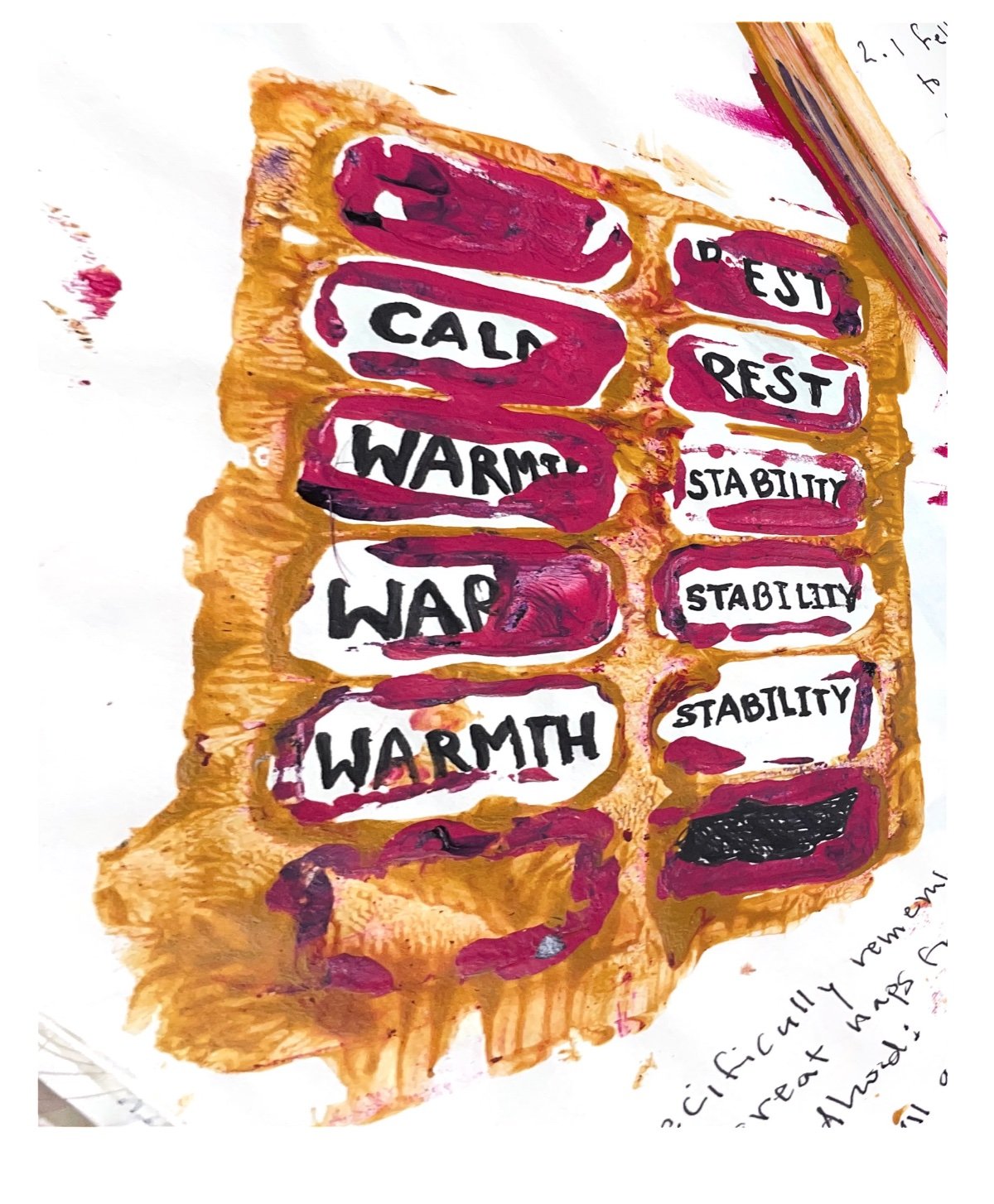

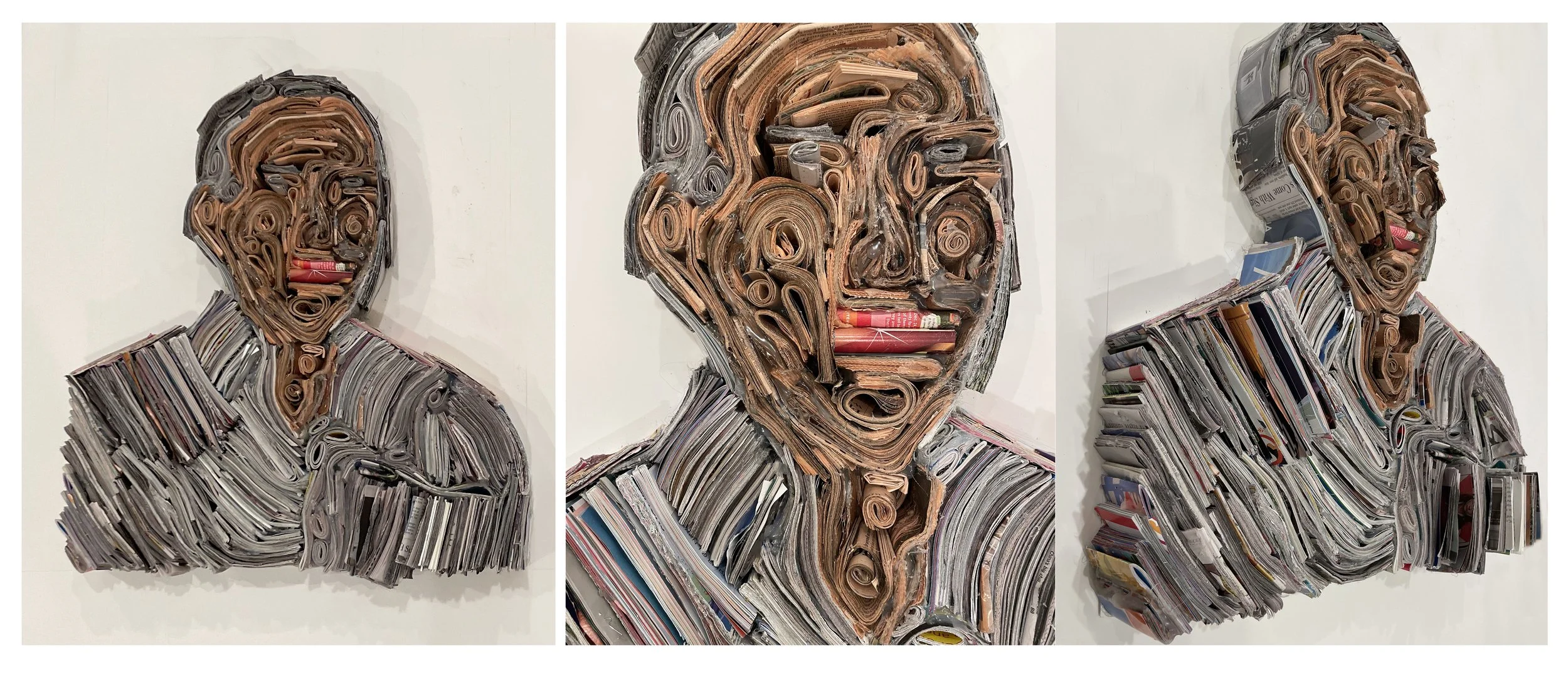

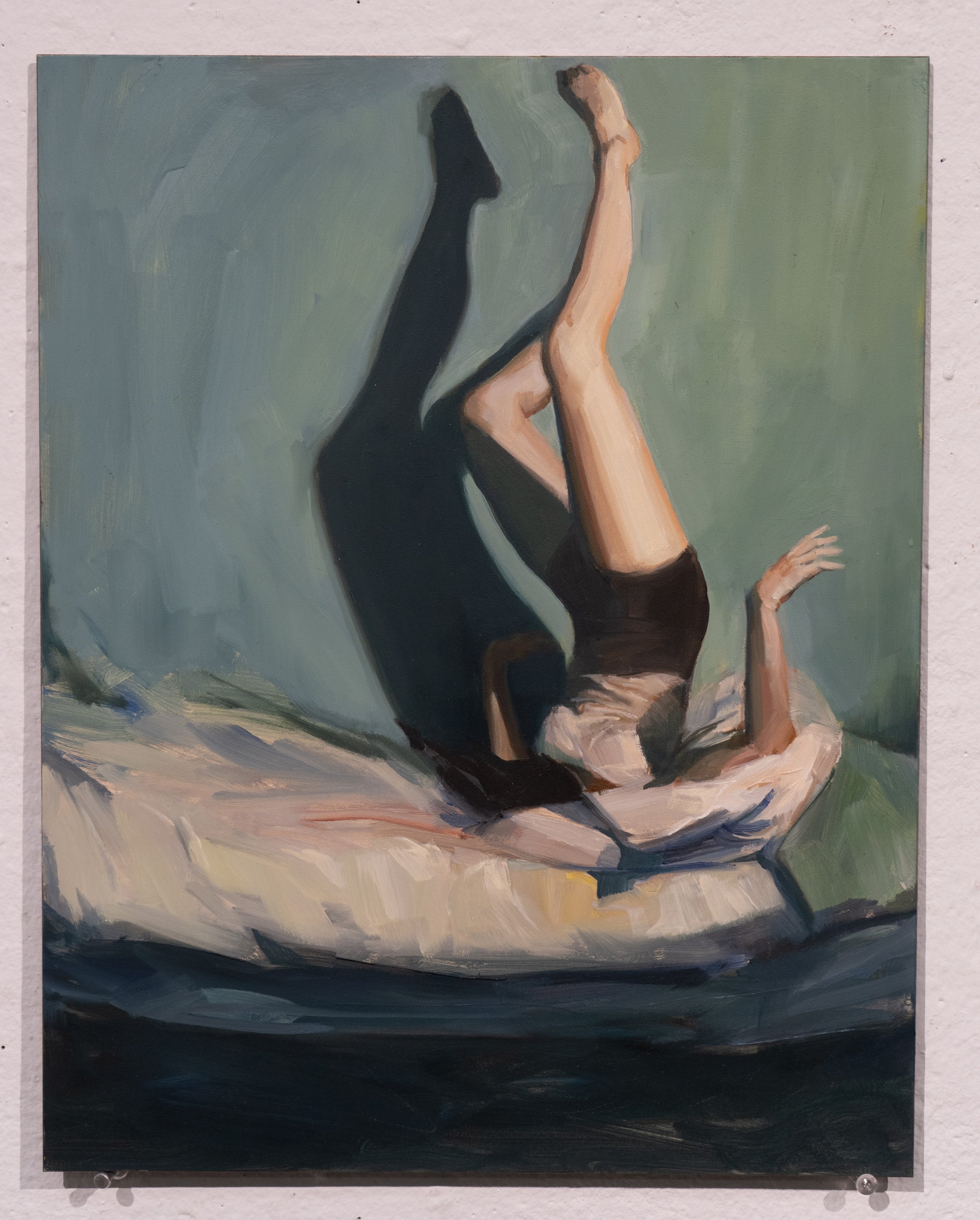

Sofía, a Barnard junior, has a command over language and a way of painting with words that feels all-consuming (and frankly, extremely intimidating. I mean, how am I supposed to write an article about a writer?). Reading Sofia’s work is a sensory experience. She writes with an abundance of scenery and description, both abstract and tangible, that does more than just help you visualize the narrative, but allows you to actually live within it. On explaining my experience reading her work, Sofía seemed a bit surprised, explaining that she just “get[s] really heavy handed.” Sofía elaborated that some of her influences include “David Foster Wallace and some Virginia Woolf, but especially the latter: I think most Virginia Woolf came after being told, ‘oh, I feel like you write like this.’ I already had established my voice, and realized ‘I also have really long sentences with a lot of adjectives’ so in school my parents, my teachers, would repeatedly make comments on my papers. One of my teachers called my sentences baroque.” As an art history student, I jumped at that – baroque is, in the best way possible, exactly how I would describe Sofía’s writing, full of simmering tension and tenebrism. Sofía continued, “there's so much to say about every given thing and I want to put everything in a sentence - and give it a color and a sound and a name and what it is about. That is what is exciting about writing to me.”

Undergirding this pathos, and giving Sofía’s writing its potency, is her commitment to writing what she sees and lives. Practically everything she writes is grounded in her own experiences, which she filters through absurdist and satirical lenses, though she cautions that, “I use those words more as adjectives than as a movement,” clarifying that she does not see herself as a Satirist or Absurdist (as proper nouns) but rather someone who plays with elements of those movements. Explaining her relationship with satire, for Sofía, satire is “a way to give an opinion, but also hide behind humor and nonchalance, to say ‘I don't care.’ Which is not always true, you can act like you don't care. You're just making a joke.” Sofía arguably began to develop her affinity for social critique in freshman year. As an international student coming from Argentina, her experience was different from many U.S. natives: “People thought I was cool on the basis of nothing. I remember feeling like I wasn't even required to have a personality because just my experience growing up somewhere else was enough material. I say ‘I've never been to Chick-fil-A’ and people would freak out.”

Sofia describes herself as being predisposed to holding back her thoughts, never the first to share an opinion nor someone who moves through the world with externalized convictions, something that people have occasionally misinterpreted: “my own hesitancy to say things about social dynamics and silence was interpreted as, ‘okay, it's cool.’ People just fill in the gaps in their brain. I think it was me doing a ground-analysis of the situation. It was also just a lot of fear, and a lot of discomfort. I was really scared to take a stance in general, and I was raised in an environment that sometimes encouraged me to be more fearful of what was new instead of curious. Taking a stance, for me, on anything, literally the smallest thing, felt like losing my ability to maneuver 360° all the time. I was staking my claim with this one particular corner of a discussion, and I didn't like that because I didn't feel like I had enough knowledge to stand behind it. It got to a point where I wanted people to know what I stand for more clearly.” Sofía did not come to writing as a form of self-expression linearly, her path was not as romantic as just “she wrote her way out of it.” It took a mix of therapy and practice - all of which diffuses into her writing to create works so thoroughly observant of the human experience. Reading her work feels like becoming another person altogether, you become so immersed in her world. Sofía’s style reads like the perfect blend between a surgeon and a surrealist - something so profoundly emotive but also deeply precise in its details.

Having heard so much about her writer’s process, I felt compelled to ask Sofía how she contends with questions about originality in her work – some artists seem obsessed with it, while others swat it off as ego-driven and impossible. After thinking for a moment, she replied, “I do think that that's something that every person who is creating something is going to grapple with. Because so much of my work is centered on my human experience, I truly focus on the exceptionality of each person and what they do. That's why I'm not necessarily as concerned with doing something that really makes me feel powerful, and that's hard.” Despite her focus on her own lived experiences, Sofía often writes as a disembodied third-person narrator, finding it to be just as personal but far more rewarding. “I'm tired of myself,” she said with a slight, exasperated roll of her eyes. “That's how I was feeling in my whole non-fiction class this semester. I had already, previously, taken another class called ‘What's Your Story.’ So, I had already been writing about myself for so long. I'd already written about my mother; our issues are well parsed out. Every time I would start a sentence with ‘I,’ I felt disgusted. That's kind of when I started writing about all these other things, because it felt like a way to talk about how I see things but not really center myself.” Out of all the brilliant things Sofía said to me at the café that day, this struck me the most. Here is a person who so sincerely experiences the world around her in prose, then uses the skills that she has worked so hard to develop to reflect the world back at itself. It is difficult to properly convey the power of the earnestness present in Sofia’s writing. (although, I suspect, Sofía could probably do it, and do it well). It is both natural and honed, as well as more deeply experiential than could ever be replicated.

On leaving Hungarian, Sofía explained, “when I got here, I never thought that I would have enough work to send it somewhere.” I looked at her, puzzled, and she explained, “I never thought that I would be chosen for someone to ask me questions about what I thought about writing, or that I would have answers.” I told her that I would call it a full-circle moment, for her to go from imagining interviews to participating in them—but for Sofía it is not, nor has it ever been, a circle, but rather a zig-zag of meaningful experiences and serendipitous accidents. Keep your eyes open for her work around campus – though be aware that if you bump into her, you might find yourself in the background of one of her pieces.